We all know that the two great certainties of life are taxes and death. But in football there is a third: bungs.

Indeed the word bung is so much part of the game today that when it appears in headlines there is no need for explanation. is was the case last week when Hull City launched a High Court action against Paul Duffen, their former executive chairman, accusing him of taking kickbacks and alleging that his company received payments from agents in return for using those agents to deal with transfers.

Time will tell whether Hull are right in believing their allegations against Duffen are watertight or whether Duffen, who insists he has done nothing wrong, emerges as the victor. Although it will be sometime before we reach the climax, what makes this case interesting is that it will be played out in the court room which is rare for such bung drama.

Interestingly the first time the word bung was used back in 1993 was also in the High Court, although the battle then was not about bungs. The word was used in an affidavit that Alan Sugar filed in his court battle for the control of Tottenham with Terry Venables.

Sugar, then chairman of Tottenham, alleged that Venables, the chief executive Sugar had sacked, had told him that Brian Clough liked a bung. What is more Cloughie liked to be paid the bungs in motorway cafes. The conversation was supposed to have taken place as the two men discussed the transfer of Teddy Sheringham from Nottingham Forest to Tottenham. Venables indignantly denied it and Clough’s reaction was, “Bngs: is that not something used to plug the bath?”

I arrate this story at some length not merely because I, along with my colleague Jeff Randall, broke the story in the Sunday Times in May 1993, but because in many ways almost everything that has happened in the bungs saga has flown from that original Sugar affidavit.

When the word bung emerges there is a lot of media attention. The great and the good in football denounce bungs and declare their determination to clean up the game. They assert that the game is basically very honest and, if bung-taking does exist, it is a minority activity not representative of football in general. At some stage an inquiry is instituted and in the end nothing happens. Football goes on as if all that has happened was the casting of an odd stone in a perfectly placid pond.

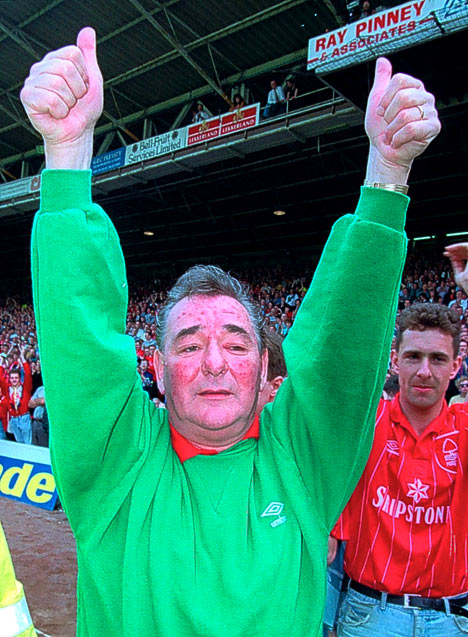

So the Sugar allegations led to a bungs inquiry, a three man team of Robert Reid QC, Rick Parry then chief executive of the Premier League, and Steve Coppell. They took their time, almost five years, but in the end all three concluded that there was a “cult of dishonesty” in the game. The problem came when deciding whether Clough (pictured) had received a bung over the Sheringham transfer. Reid and Perry were convinced he had but, despite Reid spending much time trying to convince Coppell, he refused to accept this.

So the Sugar allegations led to a bungs inquiry, a three man team of Robert Reid QC, Rick Parry then chief executive of the Premier League, and Steve Coppell. They took their time, almost five years, but in the end all three concluded that there was a “cult of dishonesty” in the game. The problem came when deciding whether Clough (pictured) had received a bung over the Sheringham transfer. Reid and Perry were convinced he had but, despite Reid spending much time trying to convince Coppell, he refused to accept this.

Coppell has never explained why and the feeling is he just could not break football’s omerta, vow of silence. The FA did charge Clough with misconduct but Clough was retiring due to deteriorating health so there was never going to be a hearing.

But that first inquiry did produce one result.

It forced the legalisation of agents. Before that agents were illegal in football and, although clubs used them and paid for them, they disguised the work they did by using highly imaginative if not false terminology to describe what they were up to.

In legalising agents football believed that it would deal with the bung culture. But the game was mistaken. Nearly a decade after the first bungs inquiry we had another one prompted by allegations of then England manager Sven-Goran Ericksson of bung taking in the game. This time the Premier League hired Lord Stevens, the former Metropolitan Police Commissioner who heads the private company Quest, to investigate.

For Stevens, investigating the Premier League clubs was a bit like looking into the books of the Vatican. As he told me, “To be frank if we had been asked to audit the Vatican we would have found a similar level of malpractice and mal bureaucracy. Some was negligence, some was failure to follow proper procedures, some indicated the system was being abused.”

Stevens highlighted some transfers and also found some evidence that he passed on to the police. This could have been money laundering in transfers but is not a matter on which Stevens can comment because his hands are tied by the criminal law of the country. “The police were already carrying out an inquiry of their own and we were duty bound if we came across any kind of criminal activity to give them the information. That is where the real rub comes in criminal law in this type of inquiry. We can’t disclose to you or anybody else what these inquiries are. Even disclosure of the terms would mean we would commit a criminal offence, that is how strong the criminal law is. The only way the evidence could come out is through court proceedings.”

The police investigation, which is still going on, may lead to criminal proceedings but as often with such matters progress is slow and the outcome uncertain. What is certain is that many in the game believe bungs are still being given but that the nature of the bung-giving has changed. It is no longer a cash payment in a motorway cafe, it is more likely to be a transfer to an offshore account. A manager may claim he has had nothing to with the transfer but the agent employed in the deal ensures that part of the fee he has received goes to the manager’s offshore account.

The police and the authorities may trace these payments but the problem here is that the very nature of football has created a climate where such bungs can be paid. Football agents are more like headhunters. This is because football does not allow the sort of headhunting common in the corporate world. In football a club which wants a player cannot just contact him directly. That would be tapping up and an illegal activity in the game. So the club turns to an agent to do it for them and then pretends that the agent is the agent of the player rather than of the club. It is this ficitious world which makes it all too easy to gain financial advantage from it.

It could be argued that football could not allow for normal headhunting of players by clubs as it would destroy the integrity of a club’s team.

What makes it worse is that many in the game fear transparency about financial dealings. It is interesting that Lord Stevens sympathises with them. He says, “The problem is football clubs are businesses. There is a commercial sensitivity which has got to be sufficient to allow trading to go on. I have sympathy with any commercial business which is trying to protect its position in the market place.”

Stevens also goes on to suggest that, for all the media attention about alleged financial wrongdoings, the average fan is more concerned with other forms of sporting misdemeanours, “I would guess the average football fan is much more concerned about somebody diving than he is about what percentage an agent gets paid as a fee. He wants his team to win and if Manchester United, or any other team, is making an acquisition that will win them titles that fan will be happy. When I go to the theatre I don’t look at the accounts to see if it is a properly run theatre. I go to watch the show.”

I have some sympathy with that view but I have always believed that the real solution to the bungs problem lies in full and complete disclosure of all transfer activity detailing payments made to agents, both their nature and their amount.

The disclosure by itself will not eliminate the payment of bungs but will act as a powerful deterrent.

In many ways I see transparency as the only solution to bungs, similar to holding up the cross to put the fear of God into Dracula.

Mihir Bose is one of the world’s most astute observers on politics in sport and, particularly, football. He formerly wrote for The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph and until recently was the BBC’s head sports editor.