We may have reached an historic moment with modern, highly paid footballers. They may finally be ready to tell the truth when they move club. The truth is that what motivates them is not the glory of the club they are going to, nor its wonderful supporters, nor even the honours they might win, but how much money the new club will put in their bank account.

I have long believed that the refrain of modern footballers, talking of a club’s ambition during transfers, has been misinterpreted by the supporters and media. It does not mean that the player is keen to know what honours the club seeks to win and how it plans to go about achieving its objectives. When a player talks of a “club’s ambition” he means the club chairman’s ambition to add noughts to his contract, even at the risk of putting the club in financial trouble as so many have done in recent years.

As football has become more of a business, you would have expected footballers to have out-grown this double-talk and to have acquired some of the straight-talking that is the hallmark of good business. Instead, even at the risk of being exposed for what they are: mercenaries moving from club to club in search of a better deal, footballers have become adept at dressing up their ambition as high-sounding moral principles.

Now, finally, a footballer is ready to come clean. Tottenham’s Emmanuel Adebayor (pictured) has admitted that, much as he would like to make his move from Manchester City permanent, he just cannot afford to do it. At City he earns around £170,000 ($265,000/€198,000) a week. The loan arrangement means City still pay the bulk of his wages – nearly £100,000 ($156,000/€116,000) – and Tottenham the rest. With Tottenham unwilling to discard its wage ceiling of around £70,000 ($109,000/€81,000) a week, a permanent move to Tottenham would mean an enormous wage cut which the Togolese is not willing to make.

True, he does say he needs the money because he sends some of it back home to help with various projects he funds. But what makes this confession special is that, for the first time I can remember, a player has discussed his possible move in money terms. He has avoided the media clap-trap that normally comes with a proposed transfer: kissing the badge of the club, declaring his knowledge of the great history of the club and his unshakable love for its wonderful supporters.

How much of a break with tradition Adebayor is making remains to be seen. But it is significant that his manager at Tottenham, Harry Redknapp, has, for months now, been telling us some footballing truths we had long forgotten or wanted to obscure. So, during problems with rival supporters, he has reminded us that there was a time when supporters did not always boo players who had left their clubs or seek to fight rival fans – they even sat with them to watch derby matches.

In his comments on what drives player transfers he has just been ready to get to the heart of the problem. So, he sees any possible move by Luka Modrić (pictured) from Tottenham to Chelsea as a move dictated by money. As Redknapp has often put it, a player offered £150,000 ($234,000/€175,000) a week, more than double what he is earning at his present club, can hardly be expected to stay. If Tottenham want Modrić to stay, then Daniel Levy, their chairman, has to show the ambition of his cheque book.

True, in the summer when the talk of such a move was at its height, it could have been argued that, given Chelsea’s success and almost permanent position in the Champion’s League, those were also factors in Modrić having itchy feet. But, at the end of the day, as Redknapp has rightly analysed, it is the riches that Chelsea’s Russian owner can offer that drove the talk of the transfer.

Redknapp, of course, is part of a generation for which such talk would have been absurd and it is interesting that, even as money started coming into football, footballers who earned less than their high profile rivals quite enjoyed being the less well paid underdogs.

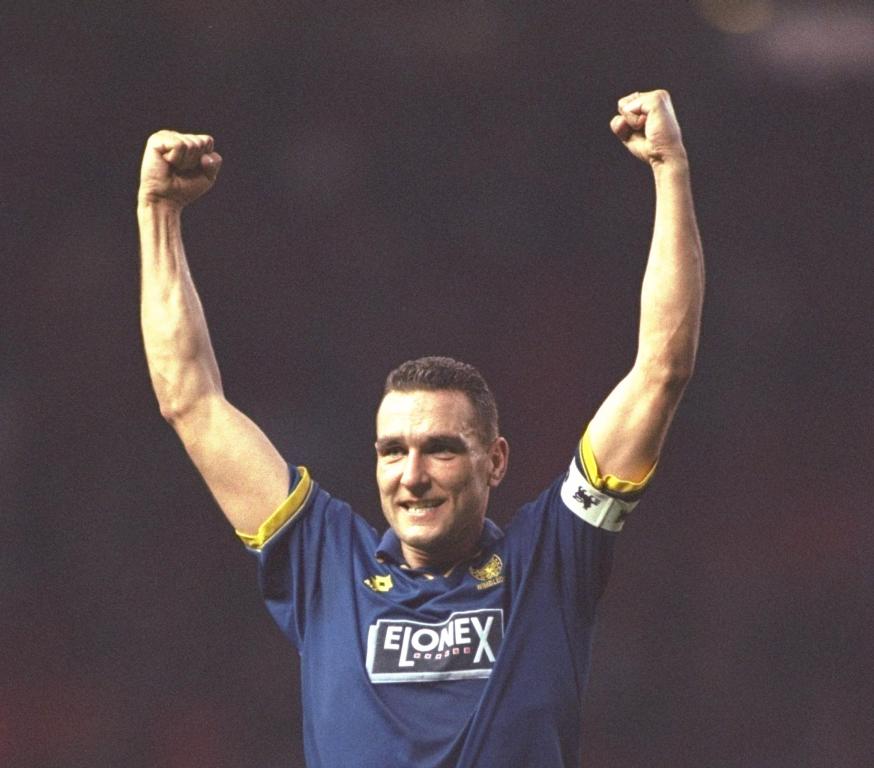

Take Wimbledon’s Crazy Gang. When they played Liverpool in the 1988 Cup Final, their players, like Vinnie Jones (pictured), were on £300 ($468/€349) a week and offered a bonus of £3,000 ($4,680/€3,491) per player if they were selected. In contrast each Liverpool player was on £10,000 ($15,600/€11,638). The nation may have wanted Liverpool to win but it was Wimbledon which triumphed driven by the fact that they were beating the fat cats.

Even that sort of money was a huge rise for the Wimbledon players. Two years earlier, Jones, on £150 ($234/€175) a week, scored a goal against Manchester United and got a £50 ($78/€58) bonus from his manager, Dave Bassett – who paid out of his own pocket. I accept that those days are gone and will never return. Clubs may model themselves on underdogs like Wimbledon but, even to reach the comfort situation in the Premier League, the differential in the wages they pay cannot be as great as back in the 1980s.

To an extent, this is a reflection of the fact that players have become entertainers. As Jones puts it, “We don’t begrudge a few million for a turn at Las Vegas so why should we begrudge modern football players.” Jones of course speaks from the comfortable position of a man who, having left football, has reinvented himself as a Hollywood film star. After 70 films, he is now on his way to becoming a producer.

There would be no problem with accepting footballers as entertainers provided they could carry that role off. The only one who has done so with any conviction is David Beckham. There has been much discussion and debate as to whether his move to LA Galaxy would finally help soccer take off in America. The jury on that is still out but my feeling is that, while Beckham has made a difference at the margins, he has not changed the basic sporting loyalty of the ordinary American sports fan.

The move was always driven by the Beckham (pictured) branding machinery. You had only to see the publicity Beckham generated as he finally won a trophy in America to appreciate how remorseless and powerful that machinery can be.

But not all footballers are Beckhams and, if they cannot clothe their materialism in high-sounding principles, then they would be much better advised to follow the lead given by Adebayor – moving jobs for money is not a sin. But pretending that a move is for the great good of the game or the club is the sort of dishonesty football can do without.

Mihir Bose is one of the world’s most astute observers on politics in sport and, particularly, football. He formerly wrote for The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph, and was the BBC’s head sports editor. Follow Mihir on twitter.