“Si monumentum requiris circumspice [If you seek his monument, look around]” Christopher Wren, epitaph on Wren’s tomb

Ever since the Great Fire of London devastated its capital, Great Britain and its inhabitants have had an obsession with architecture. It is a nation that has spawned many Great Builders, such that naming only Wren, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Sir Joseph Bazalgette or Sir George Gilbert Scott is to commit a gross injustice to the others who came before and after them.

Steve Morgan is a great builder. His achievements are of a more modest sort than his Georgian and Victorian forebears but he is a modern magnate of construction nonetheless. Redrow, the firm he founded in North Wales in the 1970s as a drainage specialist, is now a £1.66 billion house-building concern listed on the FTSE250 stockmarket.

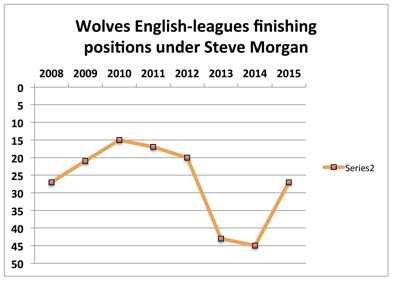

For the last seven years the 62-year-old has been the owner of Wolverhampton Wanderers, but on Monday he put the club up for sale, meaning all the major Midlands clubs – Aston Villa, Birmingham City, West Bromwich Albion and Wolves – are now on the market. More than for any of the others – who have achieved a fair amount of stability over the past decade, with several seasons in the Premier League, Wembley appearances and even a trophy to shout about – it has been a rollercoaster period for Wolves.

During Morgan’s tenure as Wolves owner they have graced three different divisions. The highpoint was two seasons’ survival in the Premier League before a double relegation took them down to League One, England’s third tier. But bouncing around the leagues is nothing new for Wolves fans.

In 1984 they dropped out of the top division and immediately suffered three successive relegations, eventually climbing back to the second tier before Morgan’s predecessor, Sir Jack Hayward, took over and brought some stability to Molineux. Not only that, his millions (70 of them ploughed in to the club by some estimates) also bought a new 31,700-capacity stadium that ensured better revenue generation to compete.

It was a sound platform, so that when Morgan took over for a token £10 with the promise of continuing Hayward’s legacy with a minimum £30 million investment in the club, fortunes soon improved. Within two seasons Wolves were champions of the Championship and had a three-year spell in the Premier League ahead of them.

Naturally that dramatically improved Wolves’ financial fortunes. But within the richest league in the world, their internal-revenue generation was no longer as impressive as in the second tier. In their first season after promotion, Wolves had the seventh-worst sponsorship, advertising and commercial income in the Premier League and the fifth-worst match-day revenues.

In 2012 Wolves’ commercial, sponsorship and advertising revenue had fallen by more than 8% but was still better than nine other clubs’. With on-the-pitch performances suffering, matchday revenues had fallen sharply by 2012 – down by nearly a quarter on 2010 levels – but there were still four clubs with lower gate and catering income than Wolves.

Morgan recognised that for Wolves to progress on the pitch, the internal revenues would have to improve. In 2010 he unveiled plans to improve Molineux. But, five years on, the computer-generated designs have never taken shape in reality.

Indeed he may have thought there was no pressing need. If the Premier League were a contest of turnover alone (and clearly it isn’t – Manchester United finished seventh under David Moyes) then Wolves would probably still be a top-flight club. After coming up for the 2009-2010 season, theirs was the Premier League’s 13th-highest turnover. In 2011 it slipped but was still the 15th, and although it fell to 17th in 2010, there were still three sides who generated less money, including Bolton Wanderers and Blackburn Rovers, who both joined Wolves in relegation.

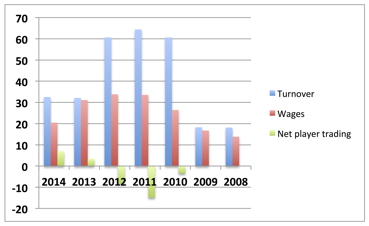

So it was not so much a deficiency of revenue generation as one of expenditure, as the table below shows.

Wolves income and expenditure under Steve Morgan

NB: Player-trading figures for seasons 2007-8 and 2008-9 are unavailable

Wolves’ under Morgan is a story of financial prudence. In their first season in the Premier League the wages-to-turnover ratio was a tiny 43.56%: lower than Manchester United’s 46.14% the same year on 4.7 times the revenue. Incredibly, this was achieved despite the £1.1 million paid to their highest-paid director – unnamed in the accounts but probably the chief executive Jez Moxey. Over their three years in the Premier League the cumulative wage bill was £93.8 million, compared to Blackburn’s £147.2 million, Bolton’s £166.4 million, even Wigan Athletic’s £117 million. (With that unnamed director taking £3.5 million in pay and pensions over the period.)

There was more adventure in the transfer market, with a net £26.7 million spent on transfers over the period Wolves spent in the Premier League but the cash surplus after core football expenditure on wages and transfers kept racking up. Over their three years in the Premier League Wolves made post-core surpluses of £65.2 million in this way. It was not as if they had debts to look after with big interest bills either as, at the end of the 2010-11 season, the club was completely debt free and had £25.5 million in the bank.

What is very interesting is how a great deal of this post-core-expenditure surplus was spent. Fully £19.9 million went on capital expenditure: real estate and infrastructure improvements. Even upon their short-lived return to the Championship, Morgan’s Wolves stumped up another £8.5 million for that in a single year.

Wolves fans will remember how he flirted with a Liverpool takeover prior to buying the Molineux club. He’s not instinctively a Black Country man. Though there is no way his strategy would have seen Wolves in England’s third tier in 2013-14 as they were, the figures show he was not prepared to break the bank for success either. There is nothing wrong with prudence, but a surfeit of it can be damaging to a club’s football success.

Now Morgan is a builder. His investment in infrastructure is more of the kind of thing that he is used to. Of course it is impossible to tell from analysis of the clubs’ accounts with whom Wolves spent all that money in their infrastructure developments. But there is no suggestion it went to any of Morgan’s personal business interests such as the Redrow company of which he owns 40%, since there are no related-party transactions listed in the audited accounts. There can be no suggestion at all of any wrongdoing in this area because what he did with his club’s money is absolutely his business.

But Morgan did not throw £30 million at the club through his boyhood love of it and is not the vanity type either. He is surely canny enough to have gained some wider benefit from his ownership of Wolves. Particularly as Redrow has since around that time been involved in a large development of executive homes in the Compton Park area of Wolverhampton worth several tens of millions of pounds. It would only be natural for local suppliers, even planners, to be better disposed to a man who owns the local Premier League football club than to a developer from outside. Who wouldn’t?

It is unlikely that another owner would derive that kind of indirect benefit from large infrastructure spending while the owner of Wolves, now a Championship club. The fact is, Morgan is a builder – a great builder – not a football man, and he has proved as much in his ownership of Wolves. But it is unlikely Wolves fans would have shared his vision for their club.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1712689683labto1712689683ofdlr1712689683owedi1712689683sni@t1712689683tocs.1712689683ttam1712689683.