Encouraging home grown players is football’s equivalent of motherhood and apple pie. You will find nobody against it. Yet no debate, at least in England, could be more absurdly framed.

This thought occurred to me when travelling on the London Underground. I was sitting opposite young people wearing sweatshirts emblazoned with the Norwegian flag. It turned out that they were not Norwegians but Italian football supporters and completely unconcerned about the foreign country whose flag they were advertising.

It was interesting that they supported rival teams in Milan, AC and Inter, but happily wandered round London together, not something I can see Arsenal and Tottenham fans doing in Milan.

But, if such globalisation is commonplace, why is it so much more problematic in English football? Consider the media backlash following last week’s Premier League match at Fratton Park between Portsmouth and Arsenal.

Let us recall that Portsmouth is foreign-owned and so, effectively, is Arsenal. The teams are also managed by foreigners.

But what got the football natives excited was not who ran the boardroom or the dugout but the nationalities on the field of play. Of the 22 players who started the match, the largest contingent was from France (seven), with 15 other nations represented by a player each. These were from: Ireland, Iceland, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Israel, South Africa, Algeria, Germany, Spain, Belgium, Russia, Cameroon, Brazil, New Caledonia, Scotland and Wales. But not a single Englishman.

Not long after the match Sam Allardyce, the Blackburn manager, turned into a preacher and warned that things were so bleak for the national team that it was time for the FA and the Premier League to “”address the situation”.

Allardyce did overegg his pudding slightly saying, “65 to 70 per cent if not more” of players in the top flight are foreign. Actually 60 per cent would be more accurate.

Where I take issue with Allardyce (pictured) is when he says in final plea, “It is British players that we want to develop. There is only the FA that can be totally responsible for all the football in this country and they have to take the bull by the horns and make sure we produce players.”

Where I take issue with Allardyce (pictured) is when he says in final plea, “It is British players that we want to develop. There is only the FA that can be totally responsible for all the football in this country and they have to take the bull by the horns and make sure we produce players.”

I am afraid, Sam, you’ve lost me. British football players? FA responsible for all football in this country? What are you talking about, Sam?

There is no such thing as British football. There cannot be. When it comes to football there is no United Kingdom.

There are four very distinct countries: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, a separation recognised by FIFA when it granted a special dispensation to the British home countries as part of the post Second World War deal which saw them return to FIFA.

And if you doubt how fiercely the home countries guard their independence, then just consider the huge problems the British Olympic Association (BOA) and the FA are having in raising a British football team for the 2012 Olympics. I am assured there will be a British team but it is unlikely to have any non-English players in it.

The fact that there is no British football nation also means that in English football the “foreigner” has always been part of the game’s landscape. The major difference is that historically the “foreigner” was one who could play for Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland. The Bosman revolution of the mid-1990s, exploiting the Treaty of Rome’s freedom of movement articles, added a further dimension making it impossible to stop clubs employing players from the foreign countries not just from other parts of the United Kingdom.

So, where once you had a Dennis Law or a George Best, neither qualified to play for England, now you have Didier Drogba and Dimitar Berbatov. Look as far back as you like and many a player in an English top flight league team, often the most important player, could not play for England.

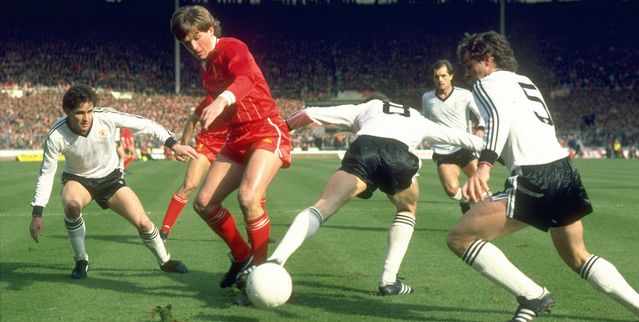

Consider the great teams of the 60s and 70s: Tottenham, Manchester United, Leeds, Liverpool and Arsenal. Who were their great players? Danny Blanchlower, Cliff Jones, John White, Dave Mackay Dennis Law, George Best, Billy Bremmer, Peter Lorimer, Ian St John, Kenny Dalglish (pictured), Alan Hansen, Frank McLintock and George Graham? All of them British but who amongst these players could or would have wanted to wear the red shirt of England? Not one.

So what has changed? Bosman has opened up the world talent pool and this has coincided with a decline in Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish talent. And, for all the talk of what can be done to encourage home grown players, there is actually quite a split in world football on this issue, in particular between FIFA and UEFA.

For more than two years, Sepp Blatter, FIFA President, has been pushing his 6 plus 5 rule to make sure more players qualified for national teams play in the domestic leagues. But, for all the noise made by Blatter and his advisers, there is little chance of this getting past the European Union. Blatter, and in particular his adviser Jerome Champagne, may every now and again produce something which suggests that 6 plus five will happen but UEFA do not want it. They consider it a closed book, fear any such proposal will lead to conflict with the EU, and cannot see how such an idea, however dressed up, can override the Treaty of Rome.

This issue also shows a wide gulf between the top teams of the Premier League and those like Blackburn who more often inhabit the bottom. Before Bosman, when UEFA had rules limiting foreign players (the infamous 3 plus 2 rule), no one was a greater critic of the system than Sir Alex Ferguson. He often had to change his team when playing in Europe and those were dismal years for Manchester United in the Champions League. For Ferguson, Bosman came as great liberator and there is no way he would like to turn back the clock.

The other factor is that English or British players are more expensive and not as good as the foreign imports. Talk to our more astute managers like Fulham’s Roy Hodgson and he will tell you that he spends hours watching Championship football. But, when he asks the price of a player, he has to say, “No thank you, I shall shop abroad.”

Tottenham are a good example. They have Gareth Bale and Alan Hutton, one Welsh the other Scottish, so they could be just the sort of British players Allardyce wants the FA and the Premier League to encourage. But they cannot get in the team because of Beniot Assou-Ekotto from Cameroon. As it happens he also cost Tottenham a lot less money.

So while saying “grow more British players” will always make good emotional headlines, it makes no sense either economically or in footballing terms. We live in a global football market and, like the Italians advertising Norway, we better get used to it.

Mihir Bose is one of the world’s most astute observers on politics in sport and, particularly, football. He formerly wrote for The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph and until recently was the BBC’s head sports editor. He will be writing a weekly column for insideworldfootball.