Football World Cups are like political elections. Just as politicians promise the earth when they want power, so a World Cup is preceded by extravagant promises by the organisers that rarely materialise.

Will South Africa be any different?

It will and it will not.

The first thing we need to disabuse ourselves of is the idea that the South African World Cup will do anything to change the way world football is run.

This will remain a game which is controlled by the Europeans, through UEFA’s Champions League and through the power of the national European leagues, where the English Premier League is so dominant. Europe will continue to provide the stage for the world’s best footballers to display their skills whether they are from Africa or South America, the modern day football version of the old story of European domination.

We need to look for changes that may take place within South Africa. And here, to rephrase that famous line from John F Kennedy’s inaugural speech, we say: ask not what South Africa will do for the World Cup, ask what the World Cup will do for the people of South Africa, the changes it has already brought and will bring.

In a sense this is, much as the Beijing Olympics was, the rainbow nation’s coming out party. But unlike China, where money was no object, the South Africans, having spent more than £3.5 billion ($5.1 billion) in putting on the party, are already gearing themselves for a hangover.

This is very evident in the warning of the Finance Minister to accounting officers of Government departments, national, provincial and municipal, that they could be held personally liable for unlawful splurging out on World Cup tickets and World Cup paraphernalia. The language which he has used, threatening them with “financial misconduct, irregular expenditure and fruitless and wasteful expenditure ” under the Public Finance Management Act, suggests that, come July 12, many in official positions in South Africa may face a very uncomfortable time.

However, while the after-party bills come in thick and fast, this may not matter if this teenager (the rainbow nation is only 16 years old) feels it has finally been accepted in the adult world and changes the internal dynamics of the country.

Here the German example may be useful. Germany in 2006 showed how a nation can profit from a World Cup, not so much in bringing economic benefits, which are in any case always overstated, but in how it shapes the German people’s image of themselves. Remember that Germany, in winning the right to host the 2006 World Cup and defeating South Africa, had coined a slogan that they felt resonated as much as South Africa’s.

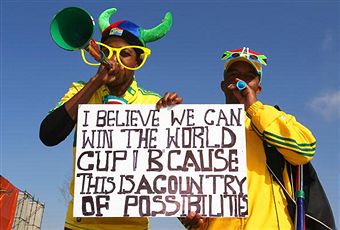

The South African slogan was that it was time Africa staged the competition, and for critics who said Africa was not ready, their response was: if not now, when? And, argued the South Africans, those who said wait were really saying the South African, indeed the African wait, would never end.

The German slogan was give a united Germany the chance to show what it can do for the world. The subtext here was that a nation which had inflicted such damage on the world deserved to show its power for good. It acquired traction as a united Germany had never held the competition. 1974 after all, was a World Cup hosted by West Germany, when German unity seemed a fantasy.

Despite this, in 2006, after nearly a decade or more of Germany finally emerging from the long shadow of the war, it took the Germans some time to show their colours. But, when they did, the nation relaxed, the Germans slowly began to display their flags, more so after the second match against Poland which carried so many historical associations. By the end of the tournament, with thousands watching on giant screens, the Germans could claim to have used football to glory in their nationalism, confident that such displays no longer threatened the national rights of other countries.

In effect, the Germans used the 2006 World Cup to address their own historical problems. It was the German nation having a dialogue as the world gathered to watch football.

And this is what the South Africans need to do and are attempting to do.

My first impression after a few days here is that the World Cup has certainly led to a lot of black empowerment. Right from the moment I arrived in the early hours of Monday morning I have been struck by the number of black faces in powers of responsibility. First at immigration and customs in Oliver Tambo airport, then at the various places where FIFA interacts with the world.

The only problem is that some of the South Africans appear to have been given a script which they follow religiously, even if it makes no sense.

Take accreditations. Now, in my experience of World Cups, this is a fairly simple process. You take your passport to a desk, your details are checked, a photograph is taken and you get a badge to hang round your neck. The badge, as such badges in all sporting completions, denotes class. If you are really important you can go anywhere inside a venue, us hacks are restricted to certain places.

Yet this time the South Africans have been insisting that, along with the passport, a letter FIFA had sent confirming accreditation be produced. Those assigned to the task have clearly been reading from a prepared script which they had memorised.

Some are so dedicated, I found when visiting a high South African official, because my credentials did not have the right boxes ticked and despite the fact that the office had sent an additional badge, I had great difficulty in getting through.

In the process, some have also shown themselves to be first timers in football in more senses than one.

This led to the situation where a certain Pele was asked which country he came from. When the greatest footballer cannot be immediately identified as a Brazilian, you realise jobs have been given to many people who are indeed very new to the game. All very good, you may say, in bringing World Cup benefits to people who have been so cruelly denied for so long.

Then there has been the laptop checks which at first were mystifying. At every venue I have been to I have had to take out my laptop much as you are required to do airports. But even more than at airports, I have had to stand and wait while an official notes down the serial number of the lap top in a book. When I have left the venues the process has been repeated with the official checking the laptop serial number against the entry made in the book.

Initially I thought this was to do with security concerns, a terrorist dumping a laptop full of devices, but it turns out to be a crime prevention measure stopping people walking away with laptops. In media centres this has led to laptops being screwed to the tables, like the old days in Fleet Street when typewriters were similarly secured.

Yet in contrast, at FIFA hotels where the great and good of world football have gathered, all this security is virtually nonexistent. At the Olympics, the IOC draws a security moat of such intensity round the hotel that getting in is almost like an Olympic competition in itself. How much of this is FIFA and how much South Africa’s desire to show its open, welcoming face to the world, I do not know. It would seem at FIFA venues, security has been increased, or gives the impression of more checks, but outside of that it is the same old smiling South Africa, unaffected by anything the modern world threatens.

Where there is no contrast with the Olympics, or indeed any other major world event, is the drive by commercial partners to make the most of it. So FIFA’s business allies are as always keen to display their wares.

I have just come from an Adidas event which was, in theory, marking the launch of the Adidas press centre. But since such an event would not draw the media, Adidas arranged for the iconic Franz Beckenbauer to come along and say a few words, which drew a huge media presence and led to a media scrum. Adidas gets the publicity, the media gets the famous name which it would otherwise struggle to get and everyone is pleased. You scratch my back I scratch yours, World Cup style.

The next five weeks will see all the other sponsors, and quite a few charities, jump on the World Cup wagon to play this game and they will judge their effectiveness by the media notice they get. Which will make this World Cup just like any other recent World Cup.

The difference is that the South Africans, who in the past have only seen this from afar, will now experience it at first hand, and, in that sense, this World Cup will mark the moment when this rainbow nation joined the modern world of sports commercialism.

Maybe that is the lesson of this World Cup. South Africa welcomes the world and realises the world of football is a huge bazaar where the object is to make sure every member of the FIFA family benefits from the bazaar. And the person who organises the bazaar does most of the paying.

Mihir Bose is one of the world’s most astute observers on politics in sport and, particularly, football. He formerly wrote for The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph and until recently was the BBC’s head sports editor. His latest book, “World Cup 2010 South Africa: the Teams, the Players, the Venues”, is available now.

.jpg)