Tottenham Hotspur’s decision to de-list from the stock market deserves more than to be buried in the footnotes as one of those curious things football club directors indulge in.

Not only is it a reversal of a policy that Tottenham inaugurated more than 30 years ago, but it also highlights that modern English football clubs have just not worked out what is the right structure for them.

What a contrast to the continent where German, or particularly Spanish, clubs are owned by members. Whatever the many headaches such democracy may cause those who run Barcelona or Real Madrid, they just get on with it and manage their clubs.

Not so English football.

The Spurs announcement came after some very good figures, which, in a normal company, would have been cause for celebration, indeed even an increased dividend: Record revenue of £163.5 million, up £43.7 million on 2010, operating profit before football trading and amortisation up by 42 per cent to £32.3 million and overall profit of £402,000 for the year up to 30 June, a big turnaround from the previous year’s loss of £6.5 million, helped by the club’s first ever Champions League campaign.

But observe the reason why chairman Daniel Levy says the club must go back to being a private company. “It is clear to us that increasing the capacity of the club’s stadium is a key factor in the continued development and success of the club and will involve the company in considerable additional capital expenditure. Given this requirement, we believe that the AIM listing restricts our ability to secure funding for its future development. We are ambitious for the club and have always taken the steps that we believe to be in its best interests.”

In other words, Tottenham desperately need money if they are to fulfil their ambition of having a new stadium that can compete with the likes of Manchester United, Manchester City and Arsenal. And for this, listing on the stock market, far from being a help, is a burden.

Indeed, the club’s finance director said as much when he pointed out that, by being listed, the club has a certain valuation. And when the men of money come to look at what they can lend, they immediately mark the sums down.

There is, of course, delicious irony in this. Back in the 1980s when Tottenham became the first football club to be listed, Tottenham’s then supremo, Irving Scholar, justified it on the grounds that it would help the club raise money and clear its debts. Scholar had come to power on the back of the financial problems caused by the development of the new stand, and Scholar, who saw himself as ahead of his times and had a certain flamboyance, saw this as football moving with the times.

Recall that this was the time when we were in the age of privatisation. All the talk was of “telling Sid” about the gas shares he could subscribe to and make a profit from. In this climate, Scholar thought offering shares in a football club would do the double: fans would get a stake in the club, and the money this would raise would take care of the club’s debt.

For a time in the 80s and early 90s this did seem the new road ahead. Tottenham’s example was followed by many other clubs. Before that, the idea that you went into football to make money would have sounded ridiculous as Peter Hill-Wood, the Arsenal chairman told David Dein. Now club chairmen and directors realised how the stock market could help them become rich.

Martin Edwards of Manchester United found this the ideal solution for him. He made a lot of money unloading his shares yet retained control for a long time, the win-win situation that many other chairmen and directors dreamt of.

Such was the belief that stock market was the way of the future that even clubs like Millwall floated on the market. I have vivid memories of going to announcements, usually in some City PR office, where directors of football clubs would wax eloquent about how their clubs made ideal stock market companies.

This is not hindsight. Even at the height of the clubs infatuation with the stock market, I had deep reservations about a football club, or any other sporting club, floating on the stock market.

Yes, the stock exchange can be a casino as much as a football match can be. But it is a very different kind of casino.

Football generates emotion. You watch your favourite team in the hope they will win, and in the process you forge bonds which go much beyond the immediate match. A club becomes more like your family. When it does well, you share its joy with this family, and when it does badly, you grieve. I may not exchange Christmas cards with my football family, but I have a bond with them which goes back into history and hopefully will carry on into the future.

That is not the case with other companies. You may hold shares in companies and hope they will prosper, provide good dividends and the share price will go up. But if this is not forthcoming and change is necessary, you will hope the board will be ruthless. There is no emotion involved. It is a practical financial decision to ensure your investment is protected.

In football, change is emotional. Removing a manager or transferring players is not just a question of discarding people who are not working. You are in the process of trading on the loyalties of your fans whose attachments with these individuals they have come to value.

Clubs have long since realised that a stock market listing does nothing for them, and there are hardly any clubs that are listed.

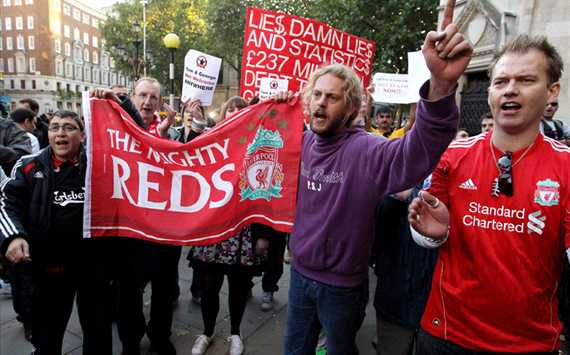

But what this has not solved is how clubs can raise money to build stadiums. Tottenham is not the only club with this problem. Liverpool have been wrestling with the problem for many years. Everton have also been on sale in the hope they will find a rich backer.

For these clubs it is a Catch-22 problem. To be successful you need to be in the Champions League always. But to get there, and stay there, you need money, which only comes if you develop yourself into a winning brand, something you cannot do without money.

And now that listing on the stock market is not a way to money, Tottenham and other clubs have to find another way of getting out of their football Catch-22.

It will not be easy.

Mihir Bose is one of the world’s most astute observers on politics in sport and, particularly, football. He formerly wrote for The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph, and was the BBC’s head sports editor. Follow Mihir on twitter.