Stuart Pearce’s Great Britain squad begin their Olympic preparations in Spain with a behind closed doors friendly against Mexico. For the only previous British Olympic team to play on Spanish soil, a place at the 1968 Olympics IN Mexico was at stake.

The Great Britain manager at the time was Football Association staff coach Charles Hughes, much later vilified for his long ball theories.

“The training was really professionally run. It was stuff that we hadn’t been used to,” said Millar Hay of Scottish amateur club Queen’s Park.

“Simple things that everyone accepts now. Training at the same time as you were playing the following night, being acclimatised, going out on to the pitch and doing your training there.”

The preparation of Hughes’ squad had begun in the summer of 1967 with a match as part of Queen’s Park centenary celebrations. It was followed by a tour of Scandinavia and Ireland.

That autumn they lost 4-0 to Celtic. Their side did not include any of the players who had won the European Cup that summer but did feature future Scottish internationals David Hay and Lou Macari.

Spain awaited Britain, only providing they beat West Germany, coached by Udo Lattek, later to lead Bayern Munich to European glory.

Hughes named his squad for the Olympic match and ordered a get together on Friday night at Bisham Abbey. The trouble was, the three Scots named – Millar Hay, Niall Hopper and Willie Neil – were needed by Queen’s Park for a Scottish League match the following afternoon. The club ordered the trio not to travel until after the match, under threat of suspension by the Scottish Football Association.

“Common sense might have prevailed a bit earlier. We were stuck in the middle really. I wanted to play the match and then go down,” said Hay.

Hughes now refused to back down and a 13-man squad (all English) travelled to the first leg in Augsburg.

‘When the three Queen’s Park lads pulled out there was no time to do anything about it,” said Peter Deadman of Barking.

“I was not fit to play but Charlie made me join the training session to make it look as though we had a full squad,” he said.

Against all odds Britain won 2-0. Although Germany won the second leg Britain were through on aggregate. Spanish eyes were also on the Olympics as they beat Iceland in their qualifier to set up the showdown.

In preparation, Britain beat Arsenal and then scored six against the Republic of Ireland. The Dagenham striker Peter Greene scored a hat-trick which did not escape the notice of the Spanish.

“The British team is a combination of very strong boys who have prepared very well. I was very impressed how they played against first division opposition. Peter Greene is a phenomenal player,” observed Spanish manager Eduardo Toba.

By now the British squad included Scots once again. Hay, one of the unwilling refuseniks in the autumn, was back in contention.

“I definitely wanted to play for the Olympic team because I wanted to get as much experience as I possibly could,” he said.

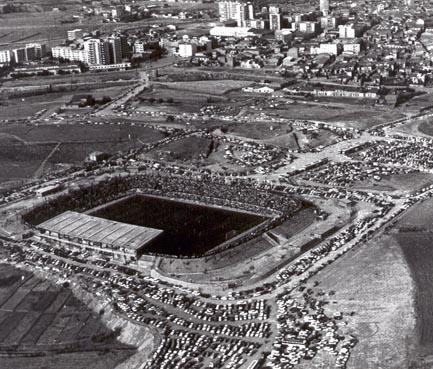

The Spanish had decided to play the match in Barcelona. It did not take place at the Nou Camp or Espanol’s Sarria stadium but at the home of Sabadell. In the newly opened Stadi Nova Creu Alta (pictured above), a capacity 20,000 generated real atmosphere.

The 19-year-old Manchester United striker Alan Gowling (pictured above, left) joined the squad. He was playing Central League football whilst studying at Manchester University and was “highly rated by Sir Matt Busby”. He went on to take his place in the first team alongside Law, Best and Charlton.

“We always believed that we could beat anyone and that was down to Charlie,” said Deadman.

The Spanish team included one notable name. Elche’s Juan Asensi (pictured above) went on to make his name with Barcelona and appeared for Spain at the 1978 World Cup. “It was a hard shift playing against a lot of players who were reserves for Barcelona,” said Hay.

The only goal of the game came in the first seven minutes. Rayo Vallecano’s 21-year-old Gerardo Ortega de Francisco headed in from a free-kick.

“The British were surprised,” said Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia. It was full of admiration for the visitors. “The British exhibited a classic approach, built on physical strength,” it said.

Spain came to London for the return leg with a 1-0 lead. It was played at the White City stadium where Britain had won their first Olympic football gold in 1908. The match was not behind closed doors but this competitive match might as well have been.

“It wasn’t a huge crowd and with the running track it was really remote,” said Hay. “There was a huge clock at either end. It was the most frustrating thing watching 90 minutes tick away and know that could have been us, we had loads of chances.”

Eric Nicholls writing in Goal magazine noted scathingly: “This performance, unimaginative in its execution, disastrous in its achievement, was the end product of three years of medical tests, psychiatric tests, endurance tests to say nothing of sifting and sorting the country’s resources in the cause of team building.”

The Spanish team of 1968 were not on the same level as their 2012 counterparts. Though they negotiated their group, they eventually lost in the quarter-finals to Mexico.

The Games were held in October so Britain’s amateur footballers were back in domestic action. The Olympics, beamed back to the United Kingdom live by satellite and televised in colour for the first time, made stars of Bob Beamon, David Hemery and Tommie Smith amongst others, but not Britain’s footballers.

Philip Barker, one of the world’s most renowned sports historians, is the author of The History of the Olympic Torch, published by Amberley recently. To order a copy click here.