“Trade has all the fascination of gambling without its moral guilt.” Sir Walter Scott, Rob Roy

When five of FIFA’s six commercial partners spoke out against the most recent corruption allegations surrounding FIFA, people across the world held their breath. Could the sponsors withdraw their financial support for FIFA? Could this effect revolutionary change at football’s world governing body?

Well, what does history tell us? Three years ago almost to the day, Adidas, Visa, Coca-Cola, Emirates and Sony all expressed their concerns about allegations the Asian Football Confederation president, Mohammed Bin Hammam, had paid cash bribes to football officials in the Caribbean. With Bin Hammam by then suspended (and now banned for life) from all football activity, Sepp Blatter was re-elected unopposed for the presidency and immediately confirmed he had come under personal pressure from sponsors to reform FIFA.

It was what led to the institution of FIFA’s independent governance committee and the beefing up of its ethics committee with twin investigatory and a judicial chambers. And as Michael Garcia concludes his investigation into historical corruption within FIFA, flowing from that reform has been the latest round of allegations about Bin Hammam and corruption by football officials around the world, published in London’s The Sunday Times.

Just like the last time, the sponsors have again issued statements on the matter. There was Visa: “We expect FIFA will take the appropriate actions to respond to the report and its recommendations.”

Then Sony called for allegations to be “investigated appropriately”. Coca-Cola added: “Anything that detracts from the mission and ideals of the FIFA World Cup is a concern to us, but we are confident that FIFA is taking these allegations very seriously and is investigating them thoroughly through the investigatory chamber of the FIFA ethics committee.”

Adidas stressed: “The negative tenor of the public debate around FIFA at the moment is neither good for football nor for FIFA and its partners.”

And finally Hyundai/Kia said: “We are confident that FIFA is taking these allegations seriously and that the investigatory chamber of the FIFA ethics committee will conduct a thorough investigation.”

But while these firms check the box of being seen to be dismayed by the actions of certain elements of the FIFA family, none of them has openly criticised FIFA or any individuals within it. There is an overwhelming message from them all that Garcia should be left to pursue his work. It is of course reasonable to accord the official process its due course. But it is when we see the extent of Garcia’s findings that the real interest begins. Will his report prove to be a mere lightning rod for FIFA? What will its commercial partners do then?

The sponsors’ financial support for FIFA is very substantial indeed, and on the face of it they wield enormous influence over the organisation. Jérôme Valcke, FIFA’s general secretary, expects FIFA’s 2011-2014 revenues to exceed US$4 billion, being more than the prior estimate of $3.8 billion, according to Sportcal.

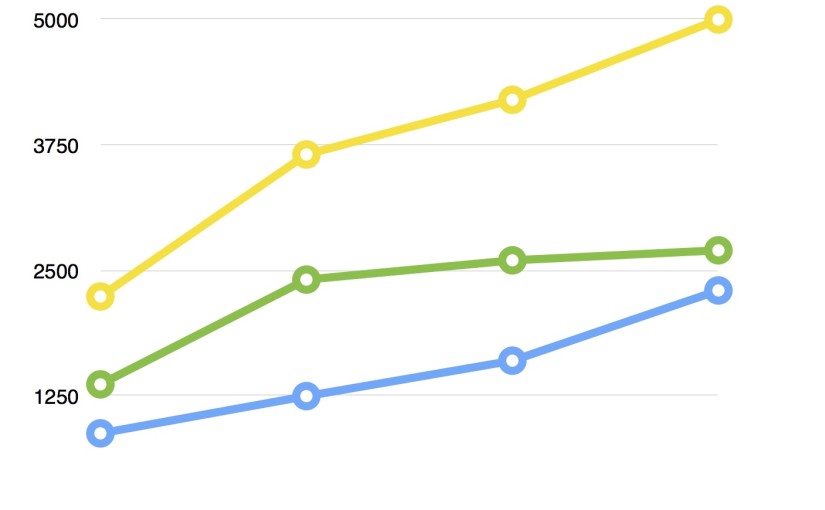

It provided a chart tracking the increase in FIFA revenue from the World Cup.

FIFA World Cup revenues (US$m) 2006-2018

Source: Sportcal

As the chart demonstrates, the value of FIFA’s World Cup marketing and commercial contracts with its partners is growing exponentially. The $2.6 billion (at least) FIFA expects to earn from that income stream in the 2015-2018 World Cup cycle is a sum more than 2.5 times higher than from the 2003-2006 period. The rise in the value of the marketing deals is, according to Sportcal, outstripping even the inflation in broadcast rights, which for other football competitions have grown at a rampant pace in recent periods.

Yet, although FIFA’s commercial revenues might constitute payments from global multinationals to a not-for-profit organisation, these are far from being charitable donations. If FIFA is going to receive on average $150 million a year from each of its six partners between 2015 and 2018 it is because what it has to offer them is an extremely valuable commodity. FIFA’s website states that being an official partner provides protection from ambush marketing by unauthorised brands as well as “preferential access to FIFA World Cup broadcast advertising”.

Since it is said that almost half of the world’s population watched at least one minute of coverage from the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, it is the opportunity for brands to receive a unique kind of exposure. Indeed for some, the FIFA World Cup is an umbilical cord.

Adidas has found it hard to satisfy investors in recent times over Nike’s increasing dominance of the sportswear market. But its chief executive, Herbert Hainer, has staved off shareholder mutiny with promises of a healthy World Cup year in 2014. Indeed, Adidas made a presentation last month that show just how important the World Cup is to his company’s business model. It anticipates $2.74 billion in annual sales from football products this year. There should be more than 13 million official World Cup balls purchased and an increase in the number of shirts Adidas is able to sell. “We want to clearly show that we are No.1 in soccer,” said Hainer. “Football is the DNA of our company.”

For the biggest consumer-facing firms there is a commercial imperative to be part of the World Cup and that is very healthy for FIFA. As Julio Grondona, the chair of the FIFA finance committee, told the Congress on Wednesday: “We have already made good progress in securing a number of partnership agreements for the upcoming commercial cycle, which is an early sign that we can expect our finances to stay healthy for the years to come.”

With the next World Cup cycle moving to Russia for the first time, if any of the sponsors withdraw from the FIFA roster there will be plenty to take their place. This pragmatically leads firms to balance their commercial interests. They must consider what is the impact on their brands of the association with an organisation that is in several parts of the world considered at best controversial. But they must also consider what impact on their global revenues rupturing with it would have.

They can walk away but will the consumers remember their moral stand when watching commercials of rival brands, ubiquitous around future World Cups? Clearly for many of FIFA’s partners the financial impact of withdrawing from their FIFA sponsorship would be negative. This restricts the leverage any of them have over the organisation.

The apparent dichotomy between perceptions of FIFA and the tournament it runs is in fact a uniting, reinforcing factor for the prevailing culture at FIFA. For as long as half the world pays attention to the World Cup, now a cultural phenomenon after 84 years, the people who run the game cannot be moved by external pressures. Even if the perceived threat were carried out by the official partners and money flushed out of FIFA, it would soon flow back in from another torrent of sponsors.

Sir Walter Scott was not entirely right: there probably is some moral guilt associated with this part of the FIFA partners’ commercial activity, but you can bet it is their fascination with trade that will matter the most.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1722043778labto1722043778ofdlr1722043778owedi1722043778sni@t1722043778tocs.1722043778ttam1722043778.