“He who seeks to regulate everything by law is more likely to arouse vices than to reform them.” Baruch Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza, the 17th Century Dutch-Portuguese philosopher, was certainly ahead of his time. His inchoate views that there is no such thing as a providential God, only nature, which one day would form the basis of his far-sighted Theologico-Political Treatise (published anonymously) were so controversial he was formally excommunicated by the Portuguese-Jewish community in Amsterdam that had brought him up.

Yet many of his views have proved by 21st Century experience to be true. The one cited above, that overbearing legal regulation can have unintended consequences that cause great damage is undoubtedly true. The Prohibition era in the 1930s US proved as much. Recreational marijuana use was legalised in four US states, tired of the deleterious consequences of the “war on drugs”, last year.

But what applies to personal vices also applies to many markets. There is without doubt a requirement for regulation to protect consumers and to prevent monopolies but it is a fine balancing act. Too much regulation can in some case be highly damaging to the regulated entity.

The Premier League is currently inviting UK broadcasters to tender for the rights to carry its matches on their channels. A decision on whom to sell those domestic rights to is expected next month. But before the Invitation To Tender could be released, one disaffected cable operator hitherto priced out of the process, Virgin, made a complaint to the regulator, Ofcom, which has now seen fit to intervene in the auction. And how it does so appears to be the only obstacle to the continued growth in the most valuable property in domestic-league football.

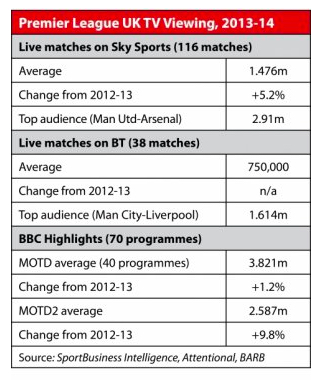

For the current three-year rights cycle the Premier League is earning £3.018 billion from UK-based broadcasters (€3.905bn, US$4.592bn) for the broadcast of 148 matches. (Overseas broadcasters add £2.5bn or €3.27bn, $3.8bn more.) The deal is split between Sky and BT, with the former taking 116 fixtures and BT 32. At £6.8 million (€8.8m, $10.3m) per match, there’s gold in thum thar hills. And the reason is it attracts a guaranteed audience of male consumers that advertisers otherwise find hard to reach. They are also prepared to pay premium subscriptions for access to it.

And exactly as for gold, contributing to the value of the property is its scarcity. Ofcom’s meddling, aimed at placating Virgin, one of its regulated entities, will reportedly lead to more matches being made available for broadcast by the Premier League. This is of course potentially dilutive in terms of price: if there is more of a commodity available it has less value.

That said, it has not stopped reports that clubs could be sharing £15 billion (€19.6bn, $22.8bn) of television revenue from August 2016 – £29.8 million (€39m, $45.3m) per match. This is frankly preposterous, particularly if Ofcom blunders in with some market- distorting intervention. Some more-realistic estimates have been for matches costing £8.8m (€11.5, $13.4bn) each, generating £4bn (€5.24bn, $6.1bn) each year for the League from the UK market.

One contributory factor in that analysis is the interest of tech companies such as Apple and Google. But that is for me a red herring. This column is far from a naysayer about tech-company entrants to the football-broadcast market. Indeed, it was here that when asked whether (Google-owned) YouTube would ever bid for football rights, Steve Nuttall, then the head of sport for EMEA at YouTube, announced: “We have found that football is the biggest sport in terms of market potential and opportunity.” [See related article below.]

So as you can see, he was not saying no. Nuttall is now the head of all content partnerships and operations at Youtube so he would have a bigger say in any such bidding today. But I am afraid I just don’t see that happening in the UK domestic market – yet. It is only when the technology of superfast broadband/4G is universally available – and capable of withstanding immense simultaneous traffic in a high-bandwidth event like a football match – that there could be a business case for YouTube or Apple to bid.

There is more of an intriguing angle in the mooted entry of the likes of Eurosport to the premium-rights market. There was talk around the FT Digital Media Conference last March that Eurosport might make a splash through the Premier League. Liberty Global, one of the biggest shareholders in Eurosport’s parent company, Discovery Communications, is also parent of Virgin. This adds a little intrigue to the recent Ofcom complaint but also would provide the opportunity for a strategic partnership between Eurosport and Virgin.

Annualised, Virgin’s most recently reported revenues were in excess of £4 billion. Sky’s, as the dominant producer of premium-football content with all the attendant advertising and subscription revenue that brings – not to mention wholesale fees from third-party carriers like Virgin – were £7.6 billion (€9.9bn, $11.5bn). Virgin, with its annual operating cash flows of about £1b billion (€1.3bn, $1.52bn), is amply equipped to bid for something even without regulatory assistance.

It is to be hoped instead that the Premier League offering of 168 games in this cycle (up from 154 before) even before Ofcom’s intervention, might be temptation enough for Eurosport and Virgin to team up over one or two packages. Perhaps with some Premier League football returning free to air on Eurosport.

Discovery’s chief executive, David Zaslav, dropped hints at that FT conference last March. “Eurosport is a bigger platform than ESPN on cable in the US and it reaches more people,” he said. “We have had a lot of conversations with a lot of players in local markets looking for partners as sports rights come up,” he said. “We will be keen to look at what is available. We are cognisant of the fact that this is a great brand. [It] could really emerge as a premier sports brand here in the UK and Western and Eastern Europe.”

The potential entrance of a big US player like Discovery could be very interesting. It might on the face of it validate some reports predicting another step change in the 2016-19 rights cycle from domestic broadcasters. But there are a number of factors weighing against it. Not least among them is that the last time a big US player came to the UK domestic market, there was genuine cost consciousness. ESPN, which had acquired Premier League rights mid-cycle from the distressed broadcaster Setanta Sports, lasted less than four years. It was priced out of the bidding for the present cycle by BT Sport.

So for all the talk of leftfield bids for the League’s UK-broadcast property from the US tech, telecoms and media giants, realistically it would seem the incumbent players are the likeliest to win out. But how far can they afford to push the needle now?

By comparing the accounts for Sky’s parent company, BSkyB, for 2012 and 2013 we can obtain a good picture of the broadcaster’s resilience to the higher expense that came from their higher bid for Premier League football. And it becomes clear that earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation were unaffected by the rising cost. BSkyB announced: “Adjusted EBITDA of £1.667 billion (2013: £1.692 billion) and adjusted operating profit of £1.26 billion (2013: £1.33 billion) is an excellent result in a period where the business absorbed a one-off step up in Premier League costs.”

Bullish though that company statement is, it seems clear that Sky could ill afford to fund another big leap in the cost of those rights as things stand. Growth-hungry shareholders do not like earnings to go flat for too long in rising markets and anything that squeezed margins further would be frowned upon.

With Sky remodelling its business in favour of in-house content production, more along the lines of the US cable giant HBO, over being a rights carrier, the likeliest outcome I would expect is for Sky to lose its position as the primary player in the rights market to BT. The former telecoms company has fought hard to gain market share from Sky, recognising that the best way of retaining and growing its core telephone-and-broadband customer base is to throw in some football too. Its BT Sport channel is free to existing residential subscribers.

BT has already committed to pay £299 million (€391m, $454m) a season to UEFA for its Champions League rights but these are a luxury offering that, played over only 25 match nights, does not constitute the basis of a viable offering to customers who want a season’s long entertainment. This suggests BT needs to expand its current offering of one Saturday 12.30pm match package.

It seems BT is keen to deliver a holistic strategy centred on its premium sports content, and it is prepared to spend big. It is in due diligence over the £12.5 billion (€16.3bn, $19bn) purchase of a mobile operator, EE, which would allow it to broadcast football to 25 million new customers, Claire Enders, the media analyst, told the Financial Times last month.

Even on its existing subscription base (which has no access to football clips or matches) that purchase would add more than £1billionn in operating cash flows to BT each year. It is the kind of thing that will drive Premier League rights values higher. The likeliest outcome, therefore, is for BT to take probably three more packages out of the seven available, forcing BSkyB to pay at least the same for less content on its Sky platform. After the 45% growth in domestic-rights values I would anticipate a rise in the order of 33% this time.

Which all makes for good news for the rightsholders, the Premier League clubs. Unless, of course there is some unnatural intervention into the market by Ofcom, arousing difficulties for what is unarguably the UK’s most successful media property. If that is allowed to happen, Spinoza will be spinning in his grave.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1751492242labto1751492242ofdlr1751492242owedi1751492242sni@t1751492242tocs.1751492242ttam1751492242.