“Whether it’s a [world] record or not doesn’t really resonate with us. What resonates is an elite player that the manager wants who is going to be a star for Manchester United.” Ed Woodward

Manchester United’s executive vice-chairman, Ed Woodward, has been pretty forthright about Manchester United’s transfer-market punch. His words have coincided with coquettish comments from the likes of Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi about how uncertain are their futures at Real Madrid and Barcelona. It has all added up to speculation that they will one day become recruits to Louis van Gaal’s red revolution at Old Trafford that has already seen Angel di María, Falcao, Daley Blind, Ander Herrera, Marcos Rojo, Luke Shaw and Víctor Valdés join.

But how likely is it, really? Several headlines have been written recently alluding to the imminent influx of cash into the United coffers through the 10-year shirt-sponsorship deal they signed with Adidas last year. It is worth a minimum guaranteed £750 million, which makes it comfortably the most valuable kit deal in world football. And this is why:

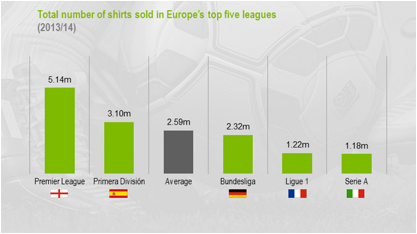

Source: Repucom/PR Marketing

According to a statement in Manchester United’s accounts, of the 5m-plus jerseys sold by Premier League clubs “approximately 2m” are United’s – about 40%. That is more than double the 875,000 the Repucom/PR Marketing report says Chelsea sell, making the London club England’s second-biggest by shirt-sales volume.

So Adidas are paying big bucks to take Manchester United away from Nike and to control the two biggest kit properties in football alongside Real Madrid. The Adidas deal kicks in next season, so when analysing United’s investment flexibility it is important to look at what impact this will have on revenues.

And the answer is: not as much as you might have thought. Although United’s contract with Adidas is open ended, few who are familiar with the detail believe it will exceed the minimum guarantees because they are so eye-wateringly huge to begin with. So let’s assume the experts are right and United pick up £75 million a year in sponsorship revenue from their shirt deal alone.

But not all of that is new revenue. As the New York Stock Exchange-listed entity, Manchester United plc, pointed out in the accounts, United made £37.5 million from Nike, their existing kit supplier, over the course of the 2013-14 season. So although they are doubling their money under Adidas, the effect of the new deal on United’s bottom line is in fact £37.5 million, not £75 million.

Interestingly, that equates almost exactly to the amount of money Manchester United will have lost this season for not competing in the Champions League, versus the sum they received from UEFA for reaching the quarter-finals as domestic champions last season. That was £37.25 million. This number is telling, because take it away from United’s £433.2 million turnover from the 2013-14 seasons and you get to the £395 million of revenue the club is projecting for the 2014-15 season. This means that the hitherto rampant year-on-year growth in commercial revenues United have been able to rely on has dried up. Indeed, that much was proven in the club’s most recent quarterly release to the stockmarket: commercial revenues were down 5.2% year over year from £59.9 million to £56.8 million.

So with internal revenue growth restricted we must turn next to the prospect of growing payments from external sources. Principal among them is the Premier League, from whom United took £89.2 million in 2013-14. But in order to achieve revenue growth from that source, United must do better on the pitch than they did last season and for now at least, despite all the new players, they are not that far ahead. Sure they are fourth this season when at the same stage they were seventh last year, but they are only three points better off. They currently have the same number of wins and the same number of goals scored as they did under David Moyes last year.

And the thing is, finishing in the Premier League’s top four and qualifying for next season’s Champions League is absolutely mission critical for England’s top clubs now. That is because the new Champions League deal from BT Sport raises the stakes for entry by orders of magnitude.

Every club entering the competition receives a “market-pool” payment according to the value of the contributions UEFA receives from that club’s national broadcast market and where they finished the previous season in their domestic league. Currently the four English clubs are paid €23.8 million for the champion, €18.7 million and €18.5 million for the second- and third-place clubs and €11.1 million for the club that came fourth. Transposing the current market-pool formula to the new deal and the values rise respectively to €54 million, €42.5 million, around €42 million and €25.2 million. In other words: they more than double. On top of that will be improved performance and participation bonuses for clubs according to their results in the competition worth conservatively an extra €35 million for a team that wins its group and is knocked out of the quarter-final.

If, as United have done, you budget to finish fourth domestically and to be knocked out in the Champions League quarter-final, and you come fifth or below in the Champions League, then the opportunity cost from next season could much exceed €60 million. Simplistically (and UEFA may very well change the formulae for next season’s tournament so this is very much a back-of-the-fag-packet calculation) if an English club enters Europe’s elite competition in 2015-16 as domestic champion and wins it, it could be worth double the €57.4 million Real Madrid picked up for winning their Décima last season.

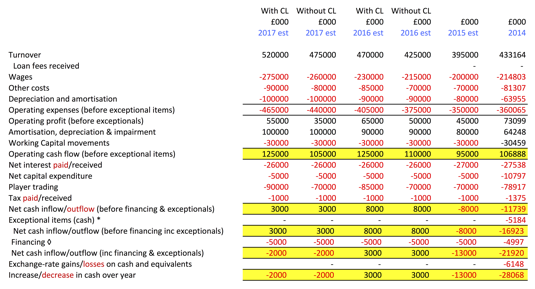

It is, therefore very important for United to be in that competition. Take a look at the numbers below. These are projections only, taking into account the estimated value of the new television deals for the Champions League for next season and also for the Premier League, which begins in the 2016-17 season. (For simplicity’s sake, the numbers assume euro-to-pound exchange rates remain the same as today’s, although I would expect them to slide further over that time.)

Now it is important to point out that this assumes the currently flatlining sponsorship revenues do not kick back into gear with more double-digit growth. This is because the table above assumes United finish in fourth place and reach the Champions League quarter-finals each year. Given their current predicament and the age profile of their current squad, this seems reasonable. It also assumes match-day revenues remain flat, which, in a deflationary environment such as now, this also seems reasonable. Naturally, should United finish champions of the Premier League and Europe each year, the numbers would change dramatically in their favour, adding perhaps £50 million a year to the numbers above in football revenues alone (and quite a lot more in commercial income too).

What the table above reflects is that despite potentially significant growth in revenues from Adidas and TV contracts, the flexibility to push the boundaries with investment in all the Ballon d’Or finalists every year just isn’t there. This is due to one element of growth that is always inevitable with the arrival of new TV contracts: rising player wages.

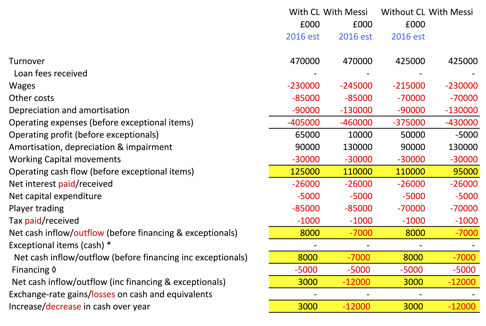

That said, signing a player like Messi, even with his €195 million buyout clause and estimated €20 million per year wages, would not be impossible. Given the tremendous size of United’s profits, it would not be an issue from the Financial Fair Play perspective. The cost of signing him could also be spread over the course of a five-year contract, making it €39 million a year. It would, however, mean that United would have to trade the players around him judiciously, since there would be perhaps £30 million of committed transfer spend on Messi already, leaving less to spend elsewhere.

What is more difficult to predict – and I have not tried to in the table above – is the kind of new revenue Messi would bring with him to United. Messi’s name would certainly sell some shirts, but that might be something of a zero-sum return, as whoever buys a Messi shirt is less likely to buy the one they would have with Wayne Rooney’s name on it.

Having Messi on the books would certainly please Adidas, whose athlete he is. But as explored before, the likelihood of a big uplift on the £75m-a-year return from their kit deal is slim. Maybe he would bring tens of millions in extra sponsorship cash from other brands. It is not since Cristiano Ronaldo in 2008 that they have had a Ballon d’Or winner (and before him not since George Best 40 years earlier). That is bound to be worth a premium to sponsors, although what they want to be associated with is enduring success, and the only way to rekindle their prior commercial-revenue growth rates is by returning to the top and winning trophies.

This is where Messi would help most. Given his reliability in front of goal, he would probably do more to push United closer to the top of the Premier League, although the arrival into a dressing room of someone so used to being the undisputed superstar wherever he goes (at least where Ronaldo is not already) would require careful management to maintain equilibrium.

So Messi is someone United could acquire. And for his name you can substitute those of Paul Pogba, Gareth Bale or Thomas Müller. That of Ronaldo though, with a buyout clause his agent, Jorge Mendes, said last year stands at €1 billion, you could not. But as such he is probably unique.

This tells us a lot about the strength of United’s finances. But another comment Woodward made, last November, about this January transfer window, spoke volumes.

He said: “We have targets that we are looking at for next summer and should any of those become available in January, which is rare, we will consider acting. But in terms of expectations we all need to recognise that’s a low probability.”

In January the following season’s Champions League participants are not known. This leads me to reflect that it is not that Manchester United could not afford Messi if they were not playing in the Champions League – they could, give or take the odd £12 million, which is more than covered by the new Premier League TV deal the following season. It is more that right now Messi, as one of the most decorated and marketable assets in the world of sport with annual commercial revenues of his own in excess of £20 million, might not think he can afford to go to Manchester United.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1751838762labto1751838762ofdlr1751838762owedi1751838762sni@t1751838762tocs.1751838762ttam1751838762.