“Nil satis nisi optimum” Everton Football Club motto

How Everton’s owners must lament that history has bequeathed them as a motto a Latin phrase meaning “Nothing but the best will do” because, since their 1995 FA Cup win, Everton really haven’t been the best at anything. But it is a stick with which to beat an underperforming club, and so it was with the acronym NSNO that disaffected Everton fans appended their banner of dissent as it flew by St Mary’s Stadium last week.

The 3-0 away victory against Southampton, a team that finished seventh last season, rather took the wind from beneath the wings of the plane of protest (hired at a cost of £2,000 – €2750, $3150 – by all accounts). Still, a thoroughly modern statement was made: ‘Kenwright & Co #Timetogo NSNO’. Two days later the chairman Bill Kenwright would be marking 24 years as a director of Merseyside’s second-most-successful club and there are no signs of him being dislodged. The aerial demonstration will prove entirely futile, of course.

The reasons are many. First of all we must ask the question: are Everton really underperforming under Kenwright? And the fact is, no they are not. If anything they are exceeding expectations. Take a look at the table below.

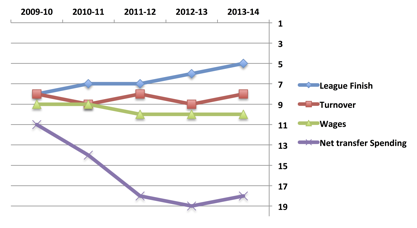

Everton’s key metrics relative to the Premier League

The most important statistic is their league position, which has been highly creditable. Between 2009-10 and 2013-14 (the most recent season for which financial data are available), Everton finished in the top eight every year, with improving returns each year. This despite having to manage the succession of David Moyes’s departure for Manchester United after 11 years in the Goodison Park dugout.

Last season, the trend dipped as the club finished 11th. But that was roughly on a par with reasonable expectations, given how the club’s wage bill had been only the 10th biggest in the Premier League. Indeed, net transfer spending had been among the bottom three for the previous three years and never in the top 10 in the previous five.

Now disgruntled Everton fans might consider this to be an area ripe for criticism. But as the old football axiom goes, the league table does not lie, and as the chart above shows, that past lack of investment did not have a particularly negative impact on football performance.

So what were the reasons for the reduced transfer activity? They can be traced back to a piece of paper signed in March 2002, when the club consolidated all its debts with Prudential with a £30 million (€41.2m, $47.2m) term loan. At the time they had more mortgages than a distressed Monopoly player: the Puma sponsorship money had been advanced, the transfer fee from Liverpool for Nicky Barmby, pretty much all of the club’s property and buildings including the Bellefield training ground. There were even third-party ownership agreements for players (which had not then been outlawed by the Premier League), with the megastore hocked as security.

All this was wrapped up instead into the new Prudential loan, for which interest payable was 7.79%. Although it was a sensible measure to consolidate the debt on fixed terms, over the 13-season period since, debt has hung heavily over Everton, taking a total of £41.3 million (€56.7m, $65m) out of the club in debt-interest service alone.

That £4 million (€5.5m, $6.3m) a year, which is what the interest load amounted to between 2009-10 and 2012-13, could have gone to pay for an £80,000-a-week (€5.5m-, $6.3m-a-year) player had Everton not been labouring under its loans. Presumably part of the reason for Everton fans’ disillusion with the Kenwright administration is that they want the board to address the amounts spent on transfers in an effort to improve football performance.

But this raises two issues. First is that in the past it was profligacy over players that caused the club’s longer-term financial headaches. The arrivals in 2002-3 of Lee Carsley, Richard Wright, Joseph Yobo, Brian McBride, David Ginola, Espen Baardsen and the blink-and-you’ve-missed-it contribution of Rodrigo Beckham (no relation) did not come cheap. These were followed up the following season with the purchases of James McFadden, Kevin Kilbane, Nigel Martyn and Joseph Yobo (a loan deal made permanent). The splurge didn’t help much at the time: they finished the 2003-4 season one place above relegation. And by now Everton’s debt was £43.3 million (€59.5m, $68.2m) – fully 97% of the club’s turnover – a gearing that had to be unwound.

This was of course achieved with the £25 million (€34.3m, $39.4m) sale in 2004 of Wayne Rooney to Manchester United, along with Thomas Gravesen’s curious transformation into temporary Galactico following his short-lived move to Real Madrid. The point here is that were Everton to go mad again, it could drive up the debt load once more. And all at a time when the rebalancing efforts of the past few years – the sales of Mikel Arteta and Diniyar Bilyaletdinov et al in 2011-12, the sale and leaseback of the Finch Farm training ground in 2013 – are finally bearing fruit.

The 2013-2016 broadcast cycle brought new riches to Premier League clubs and Everton used theirs prudently, rapidly reducing the debt burden by 38% to £28.062 million (€38.5m, $44.2m). This in turn reduced the interest payable by 18%. Most importantly, the new Premier League deal put £18.2 mllion (€25m, $28.6m) in cash in the club’s bank account, which would go a long way towards paying the £28 million (€38.5m, $44.2m) due in repayments to lenders over the course of the 2014-15 season.

By my rough estimation, Everton would only just have been able to make that payment if they marginally increased their wage bill from £69.3 million (€95.2m, $109.1m) to, say, £72 million (€98.9m, $113.3m), with a couple of million spent on infrastructure improvements and another £5 million (€6.9m, $7.9m) on transfers. This is because turnover from the Premier League fell £5 million year on year due to the weaker on-pitch performances in 2014-15. With all those costs, there would have been a total cash inflow of perhaps £9 million (€12.4m, $14.2m), pushing the club slightly into its overdraft limit as it paid down the £28 million.

As it turns out, there are signs that Everton’s past record in driving down debts has counted in their favour as the credit climate towards football clubs has been improving. It seems that with gearing now down to a very manageable 23.29%, they were able to renegotiate the repayment terms on that lumpy fee to their lenders.

Instead the cash was invested in the transfer market, with Romelu Lukaku joining from Chelsea in a big-money deal and Muhamed Besic joining from Ferencvaros. With none of the senior players leaving Goodison that season, for the first time in years Everton had become a buying club. Although that extravagant investment was curtailed this summer, with only Gerard Deulofeu rejoining the club this time on permanent terms, it is hard to see what more Everton’s board could have done.

Reloading up on debt and returning to the days of hand-to-mouth subsistence would be unwise, and a sale of the club will only be possible if a buyer can be found. The paradox is that Everton fans who call for Kenwright to move on are effectively calling for a period of transfer-market restraint as the board does everything to deleverage and shape up for sale.

What is to say that even then a buyer could be found? Sure, there are some parties sniffing around Premier League clubs but none has been able to close a deal – at Aston Villa, West Bromwich Albion or Crystal Palace. In any case, what is to say that any of them would be more benign owners for Palace than Kenwright (36.9%), Jon Woods (27%), Robert Earl (33.2%) and Sir Philip Carter (2.9%)?

Would not they be drawn to the Premier League by a profit motive? Would not their takeover be leveraged by loans and their early-splash transfer activity funded by debt, entirely repayable by the club? That has certainly been the model for other English-club takeovers. Would that not put Everton back to square one?

Kenwright and the board have to my mind done a tremendous job in the time-honoured British talent for muddling through. There have been times when the debts looked like engulfing Everton, but with judicious transfer activity and charismatic negotiation with their lenders, they’ve got by. Now, with the eighth-highest turnover in a league soon to be soaked in new cash, with debt repayments falling to boot, Everton’s future looks brighter than it has for decades.

Who knows, perhaps even the long-promised stadium-development project will one day get off the ground. Because for Everton fans, quite rightly, nothing but the best will do.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1751492202labto1751492202ofdlr1751492202owedi1751492202sni@t1751492202tocs.1751492202ttam1751492202.