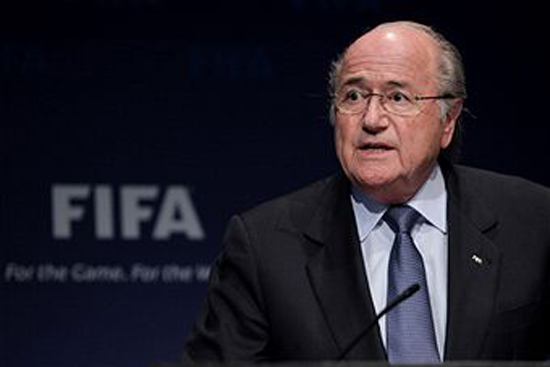

Sepp Blatter, president of FIFA, and many of his fellow executive members, may console themselves by saying that the crisis that has engulfed the organisation – both familiar and depressing – is all the fault of the dastardly British press and its nefarious ways.

They could not be more mistaken. They should look within themselves and ask why, having made the world’s most popular game into such a cash cow, they fail to run it like a proper corporate organisation where decisions are not only reached in good time, but are done so that there is sufficient transparency to prevent any possible skulduggery.

It is easy to have a go at the messenger, and the British press has always been a problem for those who run FIFA. Blatter has always believed they have it in for him. In the run-up to South Africa, he was convinced the criticism about taking the World Cup there reflected an inherent anti-Blatter British media prejudice.

Back in April, when I spoke to him, he made no secret of this feeling.

“I am always being criticised by the British media. Even when they agree with what I am saying and accept that it is a good idea of mine they go on to add ‘but this president has been under pressure on this or that’. What does that mean?”

The implication of Blatter’s remarks were clear. They may be forced to praise Blatter at times but even then it can never be full-throated approval, but must be qualified with criticisms of his alleged failings.

Blatter, in the same interview, went on to explain that the root of this problem lay in the British not coming to come to terms with the fact that they no longer run world sports: “They could not imagine that one day the leadership of sport will change to Latins.”

He has a point. Blatter may be a man who sprouts ideas almost every minute, but some of his ideas, perhaps aided by Michel Platini, have improved the game. Not all of them need be rubbished just because of the way he presents them.

And while the football in South Africa was the worst since Italia ’90, there can also be little doubt that the game as a spectacle has improved a lot in the last 20 years. This includes the no back-pass rule. Once denounced in the British media as likely to bring about the death of the beautiful game, it has actually been for the good of it.

Yet the questions that surround FIFA now are the issues of governance and there Blatter and his colleagues have not cut the mustard.

Take, for instance, the idea of deciding hosts for the 2018 and 2022 World Cups at the same session of the FIFA executive. There is a lot to be said for the idea and indeed it is hardly revolutionary. Rugby had the idea before FIFA and carried off the process for the 2015 and 2019 World Cups without any major problems. Talk to Mike Miller, chief executive officer of the International Rugby Board, and he is very proud to declare the idea made very good sense.

“It meant we could plan long term. Sponsors and advertisers could sign eight-year deals rather than just four years. It also meant we could have a strategic debate that if we choose a safe place for 2015, then we could break fresh ground in 2019. If you choose just one World Cup at a time you are always likely to choose the venue which is known. The problem then is how do you expand the game?

“The result was during the process there was much debate along the lines of if England get 2015 then perhaps Japan should get 2019. Or if South Africa get 2015 then Italy should get 2019. And that is exactly what happened, England-Japan prevailing over South Africa-Italy.”

Miler accepts the losers were disappointed, but nevertheless the whole process produced nothing like the controversy that is now surrounding FIFA decisions.

One main reason for that is FIFA has deliberately made the whole process mysterious. So while most people in FIFA readily conceded that 2018 had to come back to Europe, it kept silent. The result was that, until a few weeks ago, all the European countries were also bidding for 2022 as if to keep their options open. But almost anybody in world football will tell you that rotation may have gone but one in three World Cups must be held in Europe, the powerhouse of the game.

What stopped Blatter and his FIFA colleagues admitting this from the beginning? Then we could have had a debate along the lines – if 2018 goes to England, a safe FIFA country, then should 2022 go to the virgin football territory of Qatar, which would also take it for the first time to a Muslim, Middle Eastern country?

Instead, so mysterious was FIFA that until last week it had not even specified how the voting systems for the two World Cups would be organised. During the South African World Cup, the last chance the bids had to present their case, individual countries were still waiting for FIFA to clarify the voting rules before deciding whether to go for both 2018 and 2022, or just for one.

The result was that while during the FIFA Congress Australia withdrew from 2018 to concentrate on 2022, USA decided to wait until October when the FIFA executive would meet to decide the mechanics of the voting system.

In this column, writing from Johannesburg, I said that the voting thing was not a “trivial issue but it is actually very important. And in the race for 2018 and 2022 it could well prove quite crucial”.

I went on to say that the “decisions made at that (October) meeting will shape the deals which will decide these races. For a start, FIFA being FIFA, its voting system is not quite as laid down and rigorous as that of the IOC. Recall when Korea and Japan were bidding for 2002 and it looked as if Korea might win. João Havelange, then president, having promised Japan the competition just decided there would not be a vote. The result was that both countries shared the competition and Havelange justified it by saying it was necessary to save the face of the loser.

“Sepp Blatter, his successor, cannot quite pull off anything like that. But while in an IOC vote on bidding cities, the IOC member from the country bidding cannot vote until his or her city is eliminated, there are no such restrictions in FIFA. And this is where the voting system FIFA decides in October becomes important.”

I also went on to ask how exactly the vote might take place. “Normally, for such votes FIFA executive members are given a card with the names of the countries bidding. But with two bids being voted on at one meeting, will they be given one card or two? Remember, while all the non-Europeans, barring USA, have withdrawn from 2018, all the Europeans including England are technically still in the race for 2022, so a voting card for 2022 would also have to carry their names. And how exactly will the vote take place? They first fill in the card for 2018, then get another card and vote immediately on 2022? Or is the result for 2018 declared before they vote on 2022? All these details matter because they can make or break deals.”

The immediate response to my column were comments that deal making was not allowed under FIFA rules.

But that missed the point – which was that the voting system needed to be specified and needed to be transparent. Last week the FIFA executive, just five weeks before the vote, did specify that. However FIFA’s voting system is still not as transparent as the IOC one. There is just no explanation why this could not have been done when the decision on joint bidding was announced. It would have avoided a lot of problems.

True, by having a clearly laid out system you cannot guarantee there will be no corruption. A corruption-free voting system is a bit like asking for 100 per cent security. However, the more transparent and clear your system, the greater the chances of preventing people taking advantage of it.

FIFA’s failure to do that means that while the present rulers of football have made the game a major sports corporation, they run it as if was still a cottage industry.

The gaps this creates means it is ideal for those who seek to exploit it for their own ends.

This is what makes this crisis so worrying.

Mihir Bose is one of the world’s most astute observers on politics in sport and, particularly, football. He formerly wrote for The Sunday Times and The Daily Telegraph and until recently was the BBC’s head sports editor.

www.mihirbose.com

http://twitter.com/mihirbose