“Men yearn for poetry though they may not confess it; they desire that joy shall be graceful and sorrow august and infinity have a form, and India fails to accommodate them,” E.M. Forster, A Passage to India

When, four seasons ago, so many Manchester United fans adopted green and gold, the colours of their club’s first-ever kit, it was as a symbol of peaceful protest against the ownership of the Glazer family. The fans were moved to demonstrate their disaffection with an organisation perceived to be losing its community roots under the control of a group of remote corporate raiders.

Yet the indignation expressed in the ‘Love United, Hate Glazer’ chant is as impotent as the howl of the dog that barks at the moon. For although many fans have inherited their football colours from their forefathers just as surely as the colour of their eyes or hair, with every passing season the top end of the English game becomes less about those in the stadium and more about the warp and weft of the global economy beyond.

Almost a century after E.M. Forster chronicled the incipient demise of the British Empire, United are writing the story of their own commercial empire, one that sprawls over so many of Queen Victoria’s overseas dependencies over which the sun never set. That much became clearer than ever last week when Manchester United released its record first-quarter results for the financial year to June 30, 2014.

Headline figures showed the club’s overall income had risen 29.1% between 30 September 2012 and the same date this year. These are staggering growth rates. Over that 12-month period the UK’s gross domestic product, the income generated by the nation as a whole, increased by less than 2.2%. Indeed, over the financial quarter, Manchester United made 0.025% of every penny earned by the UK.

Frustrating though it is for the fans, this is not the locally rooted outfit that for almost 40 years before the Glazers took over was under the chairmanship of Louis Edwards and his son, Martin, men whose fortune had been made in the family meat-packing business. So what is Manchester United today?

The answer to that question is expressed by Michael Bolingbroke, United’s chief operating officer, who walked investors through the numbers in a conference call last Thursday. “In the first quarter of 2013 our commercial business represented 56.4% of our total revenues,” he said. “It now stands at 60.8%.

“Sponsorship revenue increased by a full 62.6% [over the previous 12 months] to £45.2 million due to new global and regional partnerships and the renewal of existing partnerships at higher rates.”

Alongside the uplift in the value of United’s sponsorship offering came a 40.9% rise in broadcast income to £19.3 million. With match-day income from the 75,811-seat Old Trafford stadium falling 1.5%, also to £19.3 million, it means United earn more than 80% of their money from external sources.

It still involves a football, but the 21st Century United is in business terms unrecognisable from its days under the Edwards family’s ownership. The players kicking the ball are effectively human billboards; actors on a global stage. This scene was depicted when Ryan Giggs, Rio Ferdinand and Jonny Evans attended the launch in August of United’s new sponsorship deal with India’s Apollo Tyres, a $2.5 billion-a-year manufacturing operation.

So United has become one of the most powerful brands on the planet. No longer a mere football club alone, it is effectively a 360-degree media organisation that outsources its broadcast productions to specialists and leases its name to third parties, extremely efficiently.

Thus, when Unilever, an Anglo-Dutch consumer-goods company, announced a three-year sponsorship deal with United a fortnight ago, it was not to promote its wares in Rochester or Rotterdam, rather to push its “personal care and laundry” brands by using the United crest in nine other countries. These were Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.

Given United’s and the Premier League’s positioning in south and south-east Asia, there are strong signs that the trend for chasing revenues from the region will grow still further. In September the website Sportingintelligence.com detailed figures showing how the Premier League had earned £940.8 million from its new-season broadcasting deals in the nations bookended by India in the west and Japan in the east. This was from a total overseas broadcasting income of £2.23 billion.

United and their peers like Arsenal, Chelsea and Liverpool have successfully leveraged this local interest with tours to China and other Far East nations, physically taking their brands to their biggest growth markets. This gives impetus to the virtuous circle of interest and income from the region.

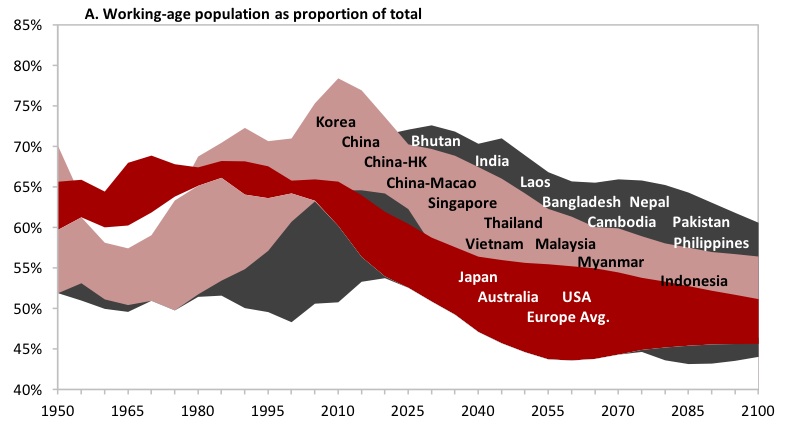

And as eyeballs in those regions are attracted, these clubs are capturing the disposable incomes of the medium-term future.

Figure A. Global working-age population as a proportion of the total (Source: Arc Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research, University of New South Wales, 2013)

Last week the Office of National Statistics released its population projections for the UK and it did not make for encouraging reading about the domestic consumer economy that football had until the Millennium relied so heavily upon.

In 2012 the UK’s population of 15- to 60-year-olds was pretty much in the middle of that red band at 59.7%; in 2037, predicts the ONS, the proportion of those in the prime working-age population will have fallen to 53.9%.

Separately, the UK Economic Outlook report published by the accountancy firm PwC last week showed that the proportion of UK household spending swallowed by housing and energy costs will have risen from little more than a quarter today to almost a third by 2030, decreasing the disposable income available for things like the football.

Another set of figures released by the ONS, this time last month, is the data on UK trade. Given the strong international element within United’s commercial turnover, it is reasonable to estimate that the club’s contribution to UK trade is almost 0.05% of the nation’s overall exports.

Table 1: Manchester United sponsors acquired during Q1 FY 2014 (Source: Manutd.com)

Company Location

Aeroflot Russia

Bulova US

Pepsi US

Apollo Tyres India

Federal Tyres Taiwan

Manda Fermentation Japan

Commercial Bank Qatar Qatar

Emirates Bank UAE

MBNA US

AFB Mauritius

Sky NZ New Zealand

True Corporation Thailand

And here is the rub: part of what attracts the overseas eyeballs (and investors) to English football is the passion of its fans, the full stadia and noisy engagement of those on the terraces. They are Forster’s poets, expressing the graceful joy and august sorrow of following their team. Many other countries fail to accommodate these emotions and seek an association with it through proxies like United.

Thus, though they might bedevil the owners with their Love United, Hate Glazer chanting, and though the value they bring in match-day revenues is falling, the fans are every bit a part of the brand and the value it carries as the Red Devil on the club crest.

So they are playing a part in the internationalisation of United and its peers at the top of the English game. Indeed, however much the paying fans resent it, it will continue unabated for the benefit principally of the clubs’ staff and shareholders. (One particularly arresting statistic from the most recent results was how core wage costs had risen £11.3 million to a level that suggests an annualised bill of £211.6 million. However much clubs earn, they seem about as adept at capping wage increases as the too-big-to-fail banks whose loans have facilitated foreign takeovers of English clubs.)

But the fans should not lament the transformation of their clubs’ commercial activities. For as the leaves continue to fall for a faltering UK domestic economy, the United fans who wrap themselves in scarves made of those autumnal colours of green and gold might reflect that their club will have to look after its human assets in the stadium. To protect their overseas revenues, United’s senior management team will have to keep their stadium full. In time economics will probably dictate that they attract the locals with the promise of cheaper tickets.

And for that to happen, the fans might thank the subsidy that has come from the far-flung corners of the former British Empire Forster described so well.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1751318999labto1751318999ofdlr1751318999owedi1751318999sni@t1751318999tocs.1751318999ttam1751318999.