“It used to be the norm for people in their early thirties to set up a home of their own, but sadly being ‘priced out’ is rapidly becoming the new norm.” David Orr, UK National Housing Federation

You might think it odd that a football business-to-business column would focus on the UK housing market but there is a lot it can tell us about our game. Not because of what we can learn about club incomes, because it doesn’t tell us much about that. Even for English top-flight football clubs the financial health of UK households doesn’t have much of a bearing on revenues. As has been discussed here before, the big Premier League clubs have a far closer eye on consumers in Asia than season-ticket holders at home.

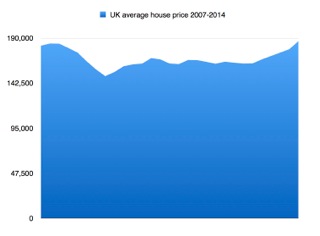

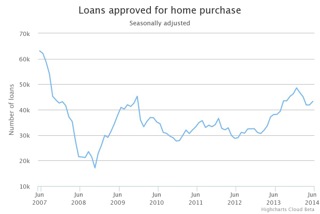

No, it is because house prices in the UK are fuelled by debt and debt is something football clubs are just as exposed to as UK homeowners. Because the housing data is far more freely available than for football transfers, it is worthwhile for us in football to look at what that debt does to the value of houses as tradable assets and extrapolate from that. And it is clear from the data that mortgage availability has underpinned the value of homes in the UK.

Check out the two charts below. They are across exactly the same timescales. The blue-block chart is UK house prices, the blue-line chart the number of home loans approved over the same period. They look pretty darn similar, with the dips in home values coming at pretty much exactly the same time as the dips in the availability of mortgages. There is a close correlation at least.

Source: Matt Scott, using Bank of England data

Source: City AM, using British Bankers Association data

Those who benefit from this dynamic are those who own lots of property outright, the cash value of which rises with the availability of mortgage loans for everyone else, and the banks who make those loans and receive regular repayment, with interest, on them. For everyone else, as is clear from David Orr’s commentary from the National Housing Federation, the picture is bleaker. Whether they be homeowners for whom an ever-greater proportion of income is lost to housing costs or those who cannot afford a house at all — those in their 20s and 30s for instance — they are ultimately left behind.

Now in football the tradable assets on clubs’ balance sheets are obviously not their homes but their players. It is very big business indeed. According to the International Centre for Sports Studies (CIES), the total value of players traded in the 2013 summer transfer window was €2 billion (£1.6bn). For the very wealthiest, as in society in general, there is often no need to raise funds from the debt markets to buy players. So when Arsenal bought Alexis Sanchez from Barcelona for a fee of about €40 million (£32vmillion) they did so from their own reserves and from the disposal of other players. This in turn helped fund Barcelona’s €80 million-odd (£64 million) outlay on Luis Suarez.

But the globalised European transfer market does not rest on the fortunes of Arsenal and Barcelona alone any more than the UK housing market rests on those of the Duke of Westminster. There are many other clubs competing for the players who are capable of putting them into the Champions League. Those clubs have varying levels of financial resource at their disposal. Indeed, few clubs with Champions League ambitions have managed their expenditure on transfer fees and wages from within their own resources alone.

Many, like homeowners, have sought funding from banks willing to pay for the investment in their future. Others, such as Everton in the Premier League, have supplemented what they can borrow against their fixed assets with creative loans from offshore lenders like the Vibrac Corporation, which until recently would routinely provide loans to the club secured against their future broadcast income.

Others still seek another form of financing, and it is one that has entered the popular consciousness in recent days. Third-party ownership (TPO) is something that has for a long time now received a lot of attention from the football authorities and those who advise them. A year ago FIFA’s general secretary, Jérôme Valcke, announced the organisation had commissioned reports from the CIES and the Centre de Droit et d’Economie du Sport (CDES) to look into the impact of third-party investment in footballers.

What they found is that US$360 million (€270m/£215m) is leaking out of football transfers to third-party investors every year. This amounts to about 10% of the total value of the global transfer market. Didier Primault, an economist at the CDES, told the French publication l’Humanité last year: “FIFA’s international regulation forbids outside influence on clubs but doesn’t talk precisely about TPO.

“The problem is that no one can truly prove influence. Since the majority of financial flows pass through investment vehicles on which the leagues have no control whatsoever, that poses a real problem. If the investment funds are majority owners of the economic rights of players whose clubs play each other, there is a risk of competition integrity that can arise.”

This is a fact FIFA acknowledges. A seminar on TPO at the annual congress in Saõ Paulo this year explained: “There is a vast heterogeneity among the stakeholders involved, such as players, clubs, players’ agents and investors in general. Operations are mainly concentrated around a few actors with considerable market power and situations of potential conflicts of interest.”

Yet despite the opacity surrounding those who invest in footballers, who typically do so from secrecy jurisdictions offshore, there is currently no meaningful regulation on TPO. Among the 106 national associations who helped formulate the CIES and CDES findings for FIFA, only three (England, France and Poland) outlaw the practice.

The fact is that financial distress has driven some clubs into the arms of third-party investors. In Brazil, where clubs have for years suffered from a lack of revenues, the practice is commonplace. Yet although the up-front cash might be useful at the point of sale of a stake in a player, it reduces the future upside when a larger fee is realised upon the player’s transfer out of the club.

There is also the wider issue of what makes third-party owners part with their cash to make the initial investment. They are making a punt on the asset value of football players, meaning they have an intrinsic financial interest in inflating transfer fees. The more the transfer market rises, the more they stand to make. Meanwhile, as less monied clubs become less able to keep up with the rising prices, the more it opens investment opportunities for the third-party owners at those distressed clubs. Even absenting the integrity threat and the potential for substantial conflicts of interest, it is a spiral that is not entirely in the interest of clubs.

At its Congress FIFA announced: “The creation of a dedicated working group under FIFA’s Players’ Status Committee … with the aim of analysing all possible regulatory options and making preliminary suggestions to the FIFA Executive Committee next September for the latter to decide on the preferred and most adequate future approach so that the working group may subsequently further elaborate on the technical details.” Phewph! In other words, it will move at a glacial pace that may or may not perhaps one day in the quite distant future eventuate in a regulatory outcome.

But in the meantime there are signs that clubs have now come to realise this TPO thing is not all it cracked up to be. Sporting Lisbon this week announced to the stock market that, upon the player’s transfer to Manchester United, they had cut their ties with Doyen Sports Investment, a fund that had owned a proportion of Marcos Rojo’s economic rights. In fact, the termination of the agreement between Doyen and Sporting seemed inevitable given the publicly volatile relationship between the two (see second related article linked below). As the “few actors with considerable market power” seek to exert a greater degree of influence, there is a strong possibility clubs will begin to resist.

Ultimately all purchasing decisions are based on a number of factors: availability not just of credit but of alternative buying opportunities and of the expectation for future gains or losses. This is true of both the transfer and housing markets alike. If clubs start to recognise that if they have to turn to TPO investment to afford a player in the first place then they have probably been “priced out” of buying him, then it will lead to a correction in player-transfer values, just as one day the UK house-price market will also correct.

Both things would cause short-term pain as homeowners default on their loans and clubs lose money on the players they have bought. But by stopping wild asset-value inflation and the overborrowing behaviour it induces, the only ones who would truly lose out in the end are the asset-accumulating elites and the lenders who strangle everyone else.

Related articles:

http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/13267-matt-scott-player-trades-boost-third-party-balance-sheets

http://www.insideworldfootball.com/world-football/europe/15253-sparks-fly-as-rojo-wrangle-causes-fury-at-sporting-and-doyen

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1751491882labto1751491882ofdlr1751491882owedi1751491882sni@t1751491882tocs.1751491882ttam1751491882.