“History… is the lesson and the example of the future,” Alphonse de Lamartine, Antar.

This time last year this column carried an annual review of 2013 by pretty much the same title (see related article below). It seems worthwhile 12 months later to recapitulate over what it said and to discover whether any of its lessons were valid.

Lesson 1: Money changes everything

Most of the league tables in the top-five European divisions looked pretty similar at the turn of last year. Halfway through the campaign the league leaders in four of the five nations had opened up a gap with the Champions League non-qualifying places to the extent they had already as good as guaranteed elite European football for this, the following season.

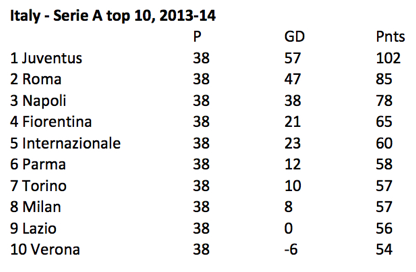

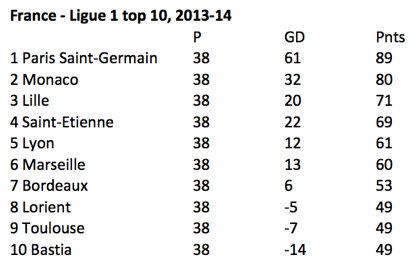

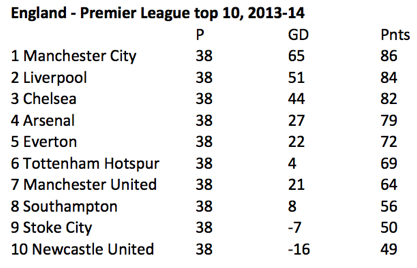

In Spain the joint leaders Barcelona and Atlético Madrid enjoyed a 17-point cushion from fifth place. In Germany it was 14 for Bayern Munich. In Italy and France it was 13 points from the highest Champions League non-qualifying position of fourth, for Juventus and Paris Saint-Germain respectively. But in England on 31 December last year the gap between Arsenal at the top and Liverpool in fifth was only six points. And while every one of the new-year’s-eve league leaders or joint leaders on continental Europe drove on to take the title, in England Arsenal could only manage to finish in fourth place, as demonstrated in the tables below.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

The gaps between title winners and Champions League non-qualifiers at the season’s end in each of the top-five leagues were: 37 points in Italy, 31 in Spain, 30 in Germany and 20 in France but in England only 14.

What I had deduced from the tables at the turn of the year was that the greater equilibrium of distribution in the Premier League mattered on the pitch, and so it seems to have been proven in the final analysis. The broadcast income generated by the highest earner, Liverpool, was only a 1.57-times multiple of what the lowest-paid club, Cardiff City, received.

Given the proportional value to Premier League clubs of broadcast incomes against their overall revenues – in 2013-14 it amounted to 77.5% of turnover at ninth-place Stoke City, for instance – this has a very strong effect on competitive balance. Clubs are more able to deploy the cash on playing staff, smoothing out the gulf between richest and poorest.

The conclusion I drew when setting this against the gaping disparity in income between Real Madrid and clubs like Levante and Hercules in Spain was that it would be wise for other competitions to tighten the spread in centrally distributed TV payments between the highest and lowest earners.

This lesson for 2014 appears to have been understood in Spain, where the president of the league, Javier Tebas, announced in November this year that Spanish legislators would debate the introduction of a law to centralise football TV-rights sales, as in England.

“Redistribution will be more equitable,” he said. “We are going to a model where between the first and last the difference will be 1 to 4.5 (against 1 to 6.5 now) and as we achieve more for broadcast-rights sales towards €1.5 billion the scale we will use is a difference between first and last of 1 to 3.5.

“We would begin with an Italian differential and end up with an English one.”

Lesson 2: Football is in a bit of a fix

Competitive balance can generate a virtuous circle: better-matched teams increase the uncertainty of outcome, generating more interest in games and a more valuable property for broadcasters to the benefit of participant clubs. But as noted in the second lesson from 2013, uncertainty of outcome cannot be guaranteed.

On Sunday, Detective Superintendent Scott Cook of the New South Wales police told reporters about the scale of the problem in Australia. “The intelligence we are getting suggests that most sports have been infiltrated [by match-fixers] to some degree, but it’s just a few people, not thousands,” said Cook.

“A lot of the information we’re getting is that players and sports people are being influenced or approached in social settings in order to manipulate them … that is one example. Other examples are when some players who have gambling problems themselves and in some circumstances we have information about players themselves organising a corrupt outcome in order for them to make money.”

The problem is far from unique to Australia. The German newspaper Der Spiegel reported that a convicted match fixer had informed it of an alleged fix at the 2014 FIFA World Cup involving Cameroon and Croatia. According to the newspaper, the Croatia win and sending-off of a Cameroon player conformed with what the match-fixer had foretold. An investigation by the Cameroonian national association, Fécafoot, was launched although its findings have never been made public.

One positive in the fight against match fixing over the past 12 months came in the shape of convictions for two match fixers, Chann Sankaran and Krishna Ganeshan, and the footballer Michael Boateng a former defender at the English non-league club Whitehawk. Sankaran and Ganeshan were handed five-year sentences and Boateng one of 16 months, all for conspiracy to commit bribery. In his summing up Judge Melbourne Inman QC said: “Professional football and sport play an important part in national life and individuals’ lives in this country.

“Those who make determined attempts to destroy its integrity for personal gain must expect significant prison sentences so when such acts are discovered a clear signal is sent to others.”

That signal may be clear but so are the potential rewards for those who fix matches. The lesson from 2013, that only when the offshore system is closed will this form of criminality be truly limited (along with many others) is, however, little closer to being realised.

Lesson 3: Soccer’s Americanisation is inevitable

Although no more major takeover deals have taken place over the course of the past 12 months it is clear that US interest in European football is growing. In October John Moores and Charles Noell, the financiers behind JMI Equity, an investment fund, were linked with a bid for Swansea City in the Premier League. At the same time Josh Harris and David Blitzer, also asset-management investors and co-owners of the ice-hockey team the New Jersey Devils, were said to be weighing up a bid for Crystal Palace.

Neither bid has yet transpired, if indeed they will at all, but as interest among US television audiences in football on that side of the Atlantic grows, the interest of billionaire investors in rightsholders on this side of ‘the pond’ is indeed inevitable. As that takes shape, it is to be expected that US investors will ultimately want football to take a form closer to that of the American sporting powerhouses such as American football, baseball and basketball.

European clubs, by formalising relationships with the football authorities through the European Clubs Association and its memorandum of understanding with UEFA, are increasingly equipped to bring that about for the financial benefit of club shareholders. The MoU increasingly permits the ECA to dictate terms to FIFA and UEFA rather than the other way round. This is because its member clubs have a big stick they could wield over the global and European confederations.

As revealed in this column in July this year (see second related article below), the MoU now expressly states ECA-member clubs are permitted to withhold non-European players from international matches in FIFA competitions. That capacity will extend to UEFA competitions from 2018, unless the MoU is extended beyond that date.

There is currently no signal at all that ECA clubs will exercise that option, but it is a useful weapon to have and shows the power the clubs increasingly hold in negotiations with other football stakeholders. Where it leads in the years to come depends on the responsibility of the actions of those who regulate the game. Otherwise an American-style self-regulation could be just as inevitable as the investment interest of the US moneymen.

Lesson 4: Epochal change is never easy

Manchester United’s epochal change, through which David Moyes replaced Sir Alex Ferguson in May 2013, would bear heavily on results, as this column noted 12 months ago. So much so that in the end Moyes did not see out the season in the Old Trafford dugout. The campaign then ended with two of Ferguson’s former protégés, Ryan Giggs and Nicky Butt, taking over as caretaker co-managers.

Next came Louis van Gaal. Charismatic, imperious and successful, the Dutchman is a manager made in Ferguson’s image – United were seeking to go back to the future. And, for the moment at least, it appears to have worked, proving that if epochal change is difficult, as little change as possible is probably for the best.

What is interesting is how the difficulties experienced at Old Trafford have coincided with more forebearance in Premier League-club boardrooms. For the first time ever in the competition’s history, all 20 clubs reached Christmas without effecting a managerial change. Although Crystal Palace have since parted company with Neil Warnock and West Bromwich Albion with Alan Irvine, it is certainly fair to say that this patience has been a virtue.

Lesson 5: Football needn’t be such a risky business

Twelve months ago Lesson 5 focused on an innovative insurance product for football that for the first time provides clubs with meaningful profit-and-loss account protection. Clubs who lose multiple players at once to injury, accident or illness risk losing millions in football income due to diminished performance. But the product in question provides guaranteed payments against the market value of players when they are unavailable. Although this insurance protection amounts to extremely sensible financial planning, I hear some clubs are choosing to self-insure instead.

This is because, as described in Lesson 1 above, clubs want to deploy as much of their available resource as possible towards the playing squad, and any euro cent spent on insurance is seen as a euro cent diverted away from that core strategy. Paradoxically, the choice to decline sensible insurance becomes clearer in a Financial Fair Play environment. Clubs who do foot insurance bills are punished by an FFP regime that does not exclude any insurance-premium payments from the break-even calculation.

But this means that if a club self-insures and its team bus, train or aeroplane is involved in an accident, the clubs are not covered for the catastrophic loss of the players involved, even as their replacement values are growing season by season. The long-term loss of, say, £150 million of players could destroy a team’s fortunes for years to come, yet directors might not have protected themselves for fear of breaching the current FFP rules.

It seems to me that taking out sensible protective measures to ensure future FFP break-even compliance – measures such as player and stadium insurance or currency-hedging arrangements – ought to be deductible from FFP break-even. Because if they are not, and clubs choose not to take them up as a result, then the consequences of catastrophes such as those seen in the recent rouble collapse or, God forbid, a terrible plane crash, could be too heavy for any club to bear.

Lesson 6: Creativity is not for the pitch alone

Twelve months ago I pointed out how clubs should think more creatively about how they generate their incomes: “Clubs should give more thought to how to make better use of their fixed assets with more creative, seven-day-a-week use of their facilities.”

English football had the opportunity to be highly creative with how the game is played and managed when in November this year the Football League held a vote over whether to permit the introduction of 3G pitches. It was a decision whose outcome might have permitted clubs to have players train at their own stadiums – perhaps freeing up land at training grounds for alternative uses – while renting out floodlit stadium space for recreational community use when the professionals do not require it.

Instead the clubs chose not to vote in favour. As other, rather less wise but still creative ways of trying to make money go further are closed down, such as the ban on Third Party Ownership coming in to force in 2015 (which was already unilaterally banned in England in any case) it would seem advisable for clubs to allow such measures. Those who voted in favour only to be thwarted by more reactionary colleagues should spend time trying to persuade them anew ahead of, perhaps, another vote in 2015.

Related articles:

Six lessons for 2014 and beyond: http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/13855-matt-scott-six-lessons-for-2014-and-beyond

Implications of the UEFA-ECA Memorandum of Understanding: http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/15081-matt-scott-when-money-can-t-buy-peace-how-history-tells-us-a-football-revolutions-is-afoot

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him moc.l1751492245labto1751492245ofdlr1751492245owedi1751492245sni@t1751492245tocs.1751492245ttamt1751492245a1751492245.