“I don’t want to be a thief of my own wallet.” Johan Cruyff

It is hard to imagine the nation that produced Johan Cruyff, Marco van Basten and Dennis Bergkamp ever giving its name to something negative in football. But then Dutch Disease is an economic concept.

Coined by the Economist in 1977, the term relates to the difficulties experienced by nations after they discover a bounteous natural resource. In the Dutch case it was a vast reserve of natural gas first tapped in 1959. The Economist noted that due to the influx of foreign currency, the guilder strengthened. Meanwhile the gas industry took up all the available skilled labour. Other domestic exporters and manufacturers withered and died.

The effect of Dutch Disease is that a great abundance of tradable commodities can be as much a curse as a blessing. Such has been seen in numerous nations across the world from Russia to Nigeria to Nauru and beyond.

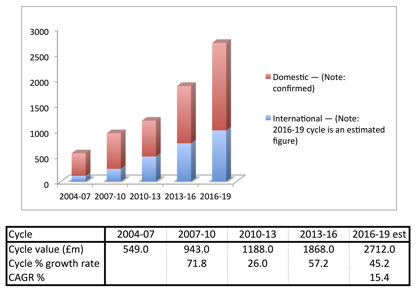

Premier League Broadcasting values 2004-2019

As with the Dutch gas men and every commodity-rich economy since, it must be tempting for Premier League clubs’ owners and executives to think the immense store of wealth they can access through broadcast rights will last forever. But nothing does last forever, and for as long as there is relegation – which every club risks by being involved in a competition from which 15% of participants are lost every year – it would be folly for many of them to assume they will be guaranteed access to those riches, even in the medium term.

Now, with the tremendous resource the Premier League has tapped through its globally leading broadcast revenues, there is perhaps a danger its clubs will succumb to similar forces. To forestall the onset of Dutch Disease, top-flight English clubs should take care to invest some of their broadcast bounty into areas that will create long-term and sustainable internal revenue generation, whether they are in the Premier League or not.

At present outside of the G6 of near-guaranteed relegation survivors (Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester United, Manchester City and Tottenham Hotspur) the bulk of Premier League clubs seem more focused on cost control than on maximising revenues. Cast your eye around the advertising hoardings of some Premier League stadiums on matchday and the local travel agent or builders’ merchant is placed alongside that of the League title sponsor, Barclays. Such sponsors are cheaply acquired but they do not represent the biggest return on the available capacity.

Premier League clubs are now global media brands with a reach into more than 200 territories worldwide and a cumulative audience measuring in the billions. Reaching out to local commercial clients with advertising space in the match programme sold in booths at the ground makes perfect sense. But putting them on hoardings viewed in tens of millions of households around the world represents a lost opportunity.

Merely using old-style fascia boards for stadium advertising is in itself an opportunity cost. Digital billboards allow software companies such as Supponor to offer advertising targeted specifically for every territory where matches are broadcast. Setting aside the capital expenditure to invest in this new technology in the stadiums would open access to commercial-revenue streams from global markets where consumer advertising is not dependent on the vicissitudes of the local economy.

Of course this does not mean there is no value in seeking local income. Some clubs have already been very effective at diversifying revenues by becoming local suppliers. Norwich City, who were a Premier League club for three years until relegation last season, belong in large part to the celebrity chef Delia Smith. Norwich’s ‘Delia’s Canary Catering’ offers fine dining on Friday and Saturday evenings and an American grill all week. These operations generate more than £4 million a year for the club. The likes of Stoke City and Sunderland make good money from their conferencing and banqueting operations – more than £3 million for Stoke and almost £6 million for Sunderland in 2013.

This demonstrates how these clubs offer unique facilities for their local business communities and high-end consumers. But there is a good deal more that could be achieved with investment. One of the big assets clubs own is the stadium. But currently they lie idle for 13 days out of 14 and for eight weeks in the summer. It needn’t be that way.

The way forward here has been signaled by American sports teams, who have transformed their stadiums from shells with seats into year-round entertainment hubs. With enormous high-definition screens, fully connected 4G and wifi-provisioned seats, US sports venues are truly 21st Century destinations. They put on concerts, gigs, rallies, trade shows and gala events. This opens opportunities for retail/commercial developments around the stadium, which in turn generate further rental and catering revenues for the sports team in a virtuous circle.

But it all requires investment – renovation or even redevelopment of the stadium itself. And that takes courage and a new mindset for football executives and owners. Given the horrific and growing cost of dropping out of the Premier League, most clubs are determined to direct every single available penny into the first-team playing squads and associated medical staffs. The understandable rationale is that since the golden goose is survival in the Premier League, feeding it with all available resources is the proper way to run a football club.

Yet there are a number of factors in which changing landscapes make this outdated. Firstly, as explored in this column last week, there are new affordable insurance products to limit the catastrophic effect of unforeseen relegation (see related article below, which will be explored in more-specific detail here at a later date). But also it should be noted that such is the magnitude of the new broadcast bounty that all 20 of the Premier League’s shareholder clubs will be among the top-40 richest in Europe. With judicious investment these clubs should be able to afford to attract playing talent sufficient to create highly competitive squads without forcing the issue with 70% wages-to-turnover ratios. With turnovers approaching the £100m-a-year level, even those who do pedal that hard should have plenty of free cash flow to invest in some worthwhile capital expenditure that will benefit the club as a diversified entertainment brand.

There are some early adopters in this defence against Dutch Disease. Tottenham Hotspur, who have put the club up for sale in search of a US investor, are in the process of redesigning their stadium accordingly. Swansea City are ready to pay £20 million to £25 million to buy the Liberty Stadium they play in from the local authority. They too are looking to attract US investment but even if they do not find it, both clubs will in time enjoy the kind of internal revenue generation that will give them the edge over rivals.

Those who do not follow suit risk being left behind or, as to paraphrase a certain Dutchman, thieving from their own wallets.

Related article: Clubs run reckless risk as revenues rise with so much resting on unprotected players — http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/16403-matt-scott-clubs-run-reckless-risk-as-revenues-rise-with-so-much-resting-on-unprotected-players

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1751420690labto1751420690ofdlr1751420690owedi1751420690sni@t1751420690tocs.1751420690ttam1751420690.