“The greatest glory in living lies not in never falling but in rising every time we fall.” Nelson Mandela

In Europe at least, falling is an ever-present risk in the game of football. Relegation makes it so. Every year in four of the top-five leagues in the UEFA jurisdiction, 15% must lose their top-flight status. It is a devastating emotional blow for all who suffer it but, due to the riches available to that division in England, the cost of failure is greatest there.

The corollary to this is that those who seek the glory of rising again are cast into a cutthroat competition that is expressed in terms of ferocious cash burn. The prize of Premier League football forces clubs to gamble spectacular sums in the attempt to attain it.

Clubs who do so are essentially bankrupting themselves on an annual basis and can only be described as going concerns due to the support of their lenders and shareholders. Indeed, retail banks have recognised the risk is too great to bear and it is only clubs with the most secure revenue streams or wealthiest owners who have been able to access finance from institutions.

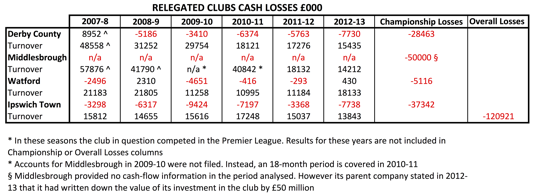

Take a look at the analysis I have produced below for four clubs that have previously been in the Premier League but fell out of it. It is immediately clear just how pernicious relegation is to the wealth of the owners of former Premier League clubs.

That is almost £71 million (€97.2m, $109.2m) of cash – not paper accounting losses, but real, hard cash – lost by three clubs over a cumulative 17 seasons. There was a further £50 million lost in accounting value over four seasons by the fourth club, Middlesbrough. (The case for Ipswich has been the most damaging, since the club has been longer out of the Premier League, their relegation having taken place a decade ago.)

Now it is possible that the financial fair play measures introduced by the Football League only in the final season of the above analysis could have an effect on the size of the differential between cash costs and revenues. Under the new regime clubs who fuel their promotion out of the Championship with excess spending risk fines equivalent to every penny overspent upon their return to England’s second tier. However looking at how Derby’s cash outflow rose 34.1% year on year in the first season of those new rules, while Ipswich’s went up a staggering 129.75%, it does not seem to have acted as a significant deterrent.

It seems, then, that what is at stake remains a tremendous amount of shareholders’ money. What has caused the destruction of so much wealth is the sharp decline in turnover that is associated with relegation. In 2007-8, Derby County’s Premier League turnover was more than three times that at the same club five years later. In 2007-8, Middlesbrough’s was more than four times bigger than five years later. As we can see, it is impossible to remain competitive while shrinking the business to fit the reduced revenues.

In the years to come, the gulf will only widen. So-called “parachute payments” to clubs who are relegated from the Premier League, which account for the graduated decline in incomes in the table above, are currently spread over four years. In the first year after relegation, clubs are paid £24 million (€32.9m, $36.9m), £19.2 million (€26.3m, $29.5m) is received in year two, and another £9.6 million (€13.2m, $14.8m) in years three and four. But even those tremendous sums do not prevent a bumpy landing when the minimum guaranteed payment in the Premier League is in excess of £60 million (€82.2m, $92.3m). Indeed, many expect that participation fee to rise north of £100 million (€137.0m, $153.9m) under the next three-year broadcast cycle, beginning in the 2016-17 season.

So if that is the frightening cost of relegation, with more than two-thirds of the Premier League season run, who should be afraid for what they will face next term? Some have stopped looking over their shoulders. Swansea City’s manager, Garry Monk, welcomed the attainment of 40 Premier League points with the defeat of Hull City on Saturday as the established watermark of survival. But even he may have spoken too soon. Swansea’s 40 points put them in eighth, but relegation is only 18 points further back. It is unlikely, but not mathematically impossible, that if Swansea do not pick up another point this season they could be overhauled by 10 or 11 sides below them.

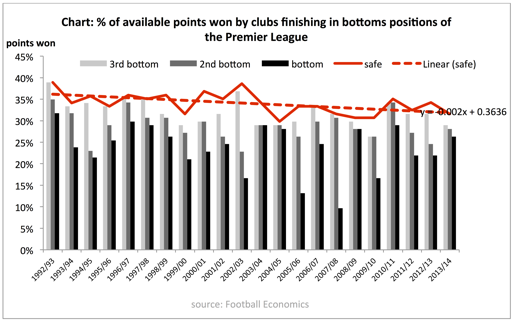

Some excellent statistical analysis by FootballEconomics.com, an independent football-specialist research organisation aimed at assisting football bodies, organisations and clubs with understanding how economic inputs affect the game, is very useful here. It shows that in 84% of the Premier League seasons since the competition’s number of participant teams was reduced to 20 in the 1995-96, 40 points has indeed been enough to ensure survival. Indeed, the number has been unassailable in every one of the past 11 completed seasons. (Due to the fact that the League has not been consistent in size, FootballEconomics.com has analysed the statistics in terms of %age of available points won by relegated clubs rather than in terms of absolute points.) The results, set out in the table below, are fascinating.

This should provide comfort not only to Garry Monk and Swansea, but also to the owners of West Ham United, who were the last club – in 2002-03 – to suffer relegation with 42 points. West Ham and Stoke City both lie in the top half of the table on 39 points. It would seem that these days, with the trend having declined over time between 1992 and today, the safety mark for survival this season is between 37 and 38 points, versus the 49 points that proved necessary when there were 22 teams in 1992-93.

As the FootballEconomics.com analyst Grant Davies points out: “Based on the trend line, a club now needs around two fewer points to stay up when compared to 10 years ago.”

With 33 still points to play for, those with 30 points and above at this stage can realistically feel relief. That leaves Everton, Hull City, Sunderland, Queen’s Park Rangers, Burnley, Aston Villa and Leicester as those with most to fear. Between them those clubs still have 66 fixtures remaining. The highest-value of those games are those that pit two of the under-threat teams together since it is an opportunity for those teams not only to win points but also to deny their rivals them. There are 13 of these “relegation six-pointers” still to play. Villa, Burnley, Everton, Leicester and Sunderland will feature in four each, with Hull and QPR in three.

QPR might be outside of the relegation zone with a game in hand but this bodes ill for them. They have won only once away from home all season – against Sunderland recently – and two of their three opportunities to disrupt a rival are away from home, at Villa and Leicester. Meanwhile their home chance is against Everton, who have lost only once against a bottom-six side away from home this season. In view of all this, if QPR were to lose all three “six-pointers” it would be no surprise.

Hull, already four points clear of relegation, look better set, playing twice at home – to Burnley and Sunderland – and away to Leicester, who have only 18 points from their 26 matches this season. Everton are better off still, with four chances to upset fellow strugglers including trips to QPR and Villa. Burnley and Sunderland should beware: Everton have lost only three times at home all season and in four matches against the bottom six at Goodison Park they have won two and drawn two, scoring nine goals and conceding only four.

Burnley might struggle at Goodison and elsewhere in these head to heads – a home fixture against Leicester is a match that must be won. Their games at Hull and Villa could prove too testing as trips to Sunderland and QPR brought 2-0 defeats. But Burnley should still not lose heart about their remaining fixtures as they are capable of getting results against any team, as their home defeat of Southampton, alongside draws at Chelsea and Manchester City proved.

Sunderland will have a big say in the final analysis, with Villa and Leicester travelling to them and trips of their own to be made to Hull and Everton. Hull have already beaten Sunderland 3-1 at the Stadium of Light this season, while Everton drew there, so points could be hard to come by in the return fixtures.

Leicester’s away days at Burnley and Sunderland could yield points, as both home matches brought draws earlier in the season but they will be looking to the home match against Hull this month, immediately after going to Manchester City, for a kickstart to the season’s run-in. If that fails then victories away to Sunderland and QPR in the final two fixtures of 2014-15 would likely be pyrrhic.

And as for Villa, upon his appointment as the new manager, Tim Sherwood set his team a target of six wins from their remaining 13 matches. But it seems from the numbers that he was applying undue pressure to his players: with 22 points already accrued, five wins and a draw could very well be enough. These are the kind of margins that make a difference. When looking at a fixtures list featuring trips to Manchester United, Tottenham Hotspur, Southampton and Manchester City, those players could be forgiven for thinking the task too tall. Instead, with home games against Everton, Burnley and QPR and a trip to Sunderland coming soon, wins in those decisive fixtures would put Sherwood well on the way to survival.

So here is for a tentative prediction: relegated this season will be Leicester, QPR and Sunderland, a combination that could at time of writing earn you 12/1 at the bookmakers. Still, if it is too much for any of them, a greater glory might lie in rising again after falling, especially where so many have expensively failed.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1751460676labto1751460676ofdlr1751460676owedi1751460676sni@t1751460676tocs.1751460676ttam1751460676.