“Thinking to get at once all the gold the goose could give, he killed it and opened it only to find nothing.” The goose with the golden eggs, Aesop

Even John Terry – that Captain, Leader, Legend of Chelsea lore, who would in time make rubble of walls with his bare thighs if his manager so desired – is not superhuman. Eight years ago even he was knocked unconscious on a football pitch, in the League Cup final at Cardiff’s Millennium Stadium. (It was against Arsenal, so inevitably Chelsea still won.)

Most footballers have frailer frames than that of the Romford-born former England captain. The physical exertions of the Premier League forbid almost all others to go, as he did last season, through the whole campaign without missing a minute.

This is what compelled Chelsea’s doctor Eva Carneiro to enter the field of play on Saturday to attend to an apparently injured Eden Hazard. Her intervention has invoked the wrath of Jose Mourinho, who has apparently made it clear the doctor must be demoted to a background role away from the stadium.

It has been a public crucifixion for Carneiro and the Chelsea physio, Jon Fearn, and the chief executive of the Football Medical Association, Eamonn Salmon, leapt to their defence. “They conducted themselves with integrity and professionalism – that is their job,” said Salmon. “We feel that she has been treated harshly.”

And so she has. The fact is: Carneiro has a duty of care to her patient. But what is being missed in Mourinho’s wrath towards her is that Carneiro’s duty also extends to her employer. In her hands lies not just a human being, indeed not just a fabulous footballer, but also an asset worth perhaps €100 million to Fordstam Limited, the parent company of Chelsea. Fearn and Carneiro must make sure injured players receive the highest standard of first aid. It is the basis of their job.

If a player suffers a career-threatening injury – a double fracture in the leg maybe, or multiple simultaneous cruciate-ligament ruptures – then tens of millions of pounds of asset value are at stake. The fact that on the occasion in question Hazard had mercifully not suffered a serious problem is not really relevant. It is a simple fact that the health of players is fundamental to the health of a club’s balance sheet.

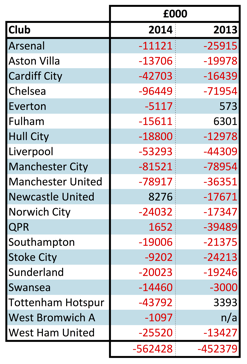

We only have to look at the amount of money Premier League clubs have spent on player recruitment in recent years to see just how big a deal player injuries can be. Below is a table of spending over two years for the 20 clubs who were in the Premier League during 2013-14, the most recent season for which figures are available.

2013-14 season Premier League clubs’ net spending on player transfers

The numbers above demonstrate the exact cash amount spent on new players after players were sold. Over the two seasons, more than £1 billion (€1.4bn, $1.56bn) was spent by those Premier League clubs. Hazard joined Chelsea during a season of £71.9 million (€100.7m, $112.3m) of net spending at Stamford Bridge, suggesting he already commanded an enormous value even before his double Premier League FWA Footballer and PFA Player of the Year prizes in 2015.

Indeed, the £1billion two-season total does not even account for players purchased before 2013 or those produced by the clubs themselves. In Arsenal’s statutory accounts for instance, Jack Wilshere has a value of £0 but his market value should they come to sell him would be tens of millions. This proves just how much risk clubs are exposing themselves to every time their players set foot on a training ground, a football pitch or in an international match. As transfer fees rise fast towards nine-figure sums, clubs’ ability to replace key players from within their own resources is reduced.

With Financial Fair Play [FFP] restricting the flexibility for investment in the transfer market, a sequence of serious injuries or illnesses could buckle a Premier League club’s prospects of making the Champions League or, worse, even of surviving relegation. In such cases, there becomes a need for external financial assistance to cover unexpected expenses.

Let’s imagine a £20 million player has recently returned from major injury to training. The medical staff recommend the player continues to regain match fitness for the following week but the manager insists the player returns for an important game. The injury recurs, forcing the player out for months and possibly into an early retirement.

At a human level that’s a sad state of affairs, but at a business level it’s disastrous and hugely costly. Managers need to win games, but the club has a need to manage the financial risks it takes accordingly. There is a link and a tension between what it takes to win games, with all the attendant financial rewards, and the cost incurred when injuries are suffered. How clubs manage this balance is a hugely important process. Yet it would seem from Mourinho’s actions this week that at Chelsea at least it is the manager, with all his short-term motivations, who has the rudder hand.

In the commercial world, any outsized risk exposure would be transferred to major insurers. If a hotel firm had a portfolio of 25 revenue-generating assets, as does a football club, it would reserve an annual amount for unforeseeable losses, and then insure the balance of the exposure against a disastrous, unmanageable run of luck that might put one or more of them out of action. Yet despite the extreme risks intrinsic to putting a multimillion-pound footballer in the firing line of opponents’ tackles twice a week, the insurance available to football clubs has traditionally been limited.

There is insurance that will pay wages in the event of a player’s injury absence (known as “temporary total disablement” [TTD] cover) but that has no value since player wages are specifically budgeted for and are payable from within guaranteed revenues, come what may. Then there is insurance that pays out against the value of a player’s retirement through injury (‘permanent total disablement’ [PTD] cover) but this, too, is poorly regarded by the clubs since so few players ever do hang up their boots in this way.

The likes of Michael Owen or Owen Hargreaves, debilitated though they were in the latter part of their careers, were able to find good clubs on the basis of their prior reputations. A club that takes out PTD cover has no guarantee that the cover will work. In both cases, the cover is so littered with exclusions that very seldom do clubs receive any payout at all. If a player has previously suffered, say, a cartilage injury to the left knee then all problems with the left knee will likely be excluded under the policy. So if he subsequently suffers an entirely unrelated anterior cruciate ligament rupture or dislocated patella, that’s tough – the insurer won’t pay.

And so the issue of what to do if three or four players suffer major injury problems all at once remains. Last season Chelsea won the Premier League after using seven outfield players from the start in 34 matches or more [see related article below], which was quite a feat of plate-spinning by Carneiro and Fearn in the Chelsea medical department.

What to do if Hazard, Diego Costa, Willian and Thibaut Courtois all suffer career-threatening injuries in a single season and Chelsea are unable to qualify for the Champions League? Football revenues would be substantially reduced and the ability to replace them would similarly fall. In an FFP world, the old recourse to Roman Abramovich’s riches would be closed. Traditional insurances would fail to support the club in their hour of need.

The insurance market, spurred on by seeing the tremendous growth in the games revenues and attendant exposures has begun to respond. I am aware of at least one major new coverage that offers clubs £100 million of coverage against all major injuries to any player within the squad.

Clubs increasingly – sensibly – are setting about reviewing their risk outlook and strategies to counter it. The question is are they also managing this risk internally through designing protocols whereby the financial responsibility associated with the players is not in the manager’s jurisdiction but in the hands of an overarching risk-management policy? That certainly does not seem to be the case at Chelsea.

Mourinho showed with his response to Carneiro’s intervention how he has a winner’s attitude to every single minute of a football match. As the manager, he is necessarily greedy for success. But as such he is the Attacus Greeb of the piece, the avaricious farmer in Aesop’s Fable.

If he or managers like him push their players too hard in pursuit of the success they are contracted to provide, then the injury risks rise to the extent that the golden goose may be killed. Then it is not the manager who ultimately pays – for even if he is sacked he will always find another job – but the shareholder whose balance sheet has been at daily risk on the training ground and football pitches.

Related article: http://www.insideworldfootball.com/matt-scott/17531-matt-scott-jose-is-talking-piffle-but-can-he-do-without-the-presents-of-the-past

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1722059530labto1722059530ofdlr1722059530owedi1722059530sni@t1722059530tocs.1722059530ttam1722059530.