Consider this question. In the next few years Britain may decide to leave the European Union. At no time since this country joined what was then the Common Market 40 years ago has there been such a strong anti-European feeling. And this is a mood that seems to be going beyond the traditional ‘fed up with Brussels’ to ‘get out of Europe’ clamour.

But even should a referendum see the people of Britain vote to leave, one thing that cannot be reversed is the Europeanisation of English football. Indeed my prediction is that should such an eventually come to pass in say in two or three years time it may well coincide with the moment when this country’s football follows down the ultimate continental route and introduces a winter break. It will be the final proof that Britain may have left Europe and returned to its island fastness but the country’s national game will always carry the marks of European football ideas. What is more those marks can never be erased.

Impossible?

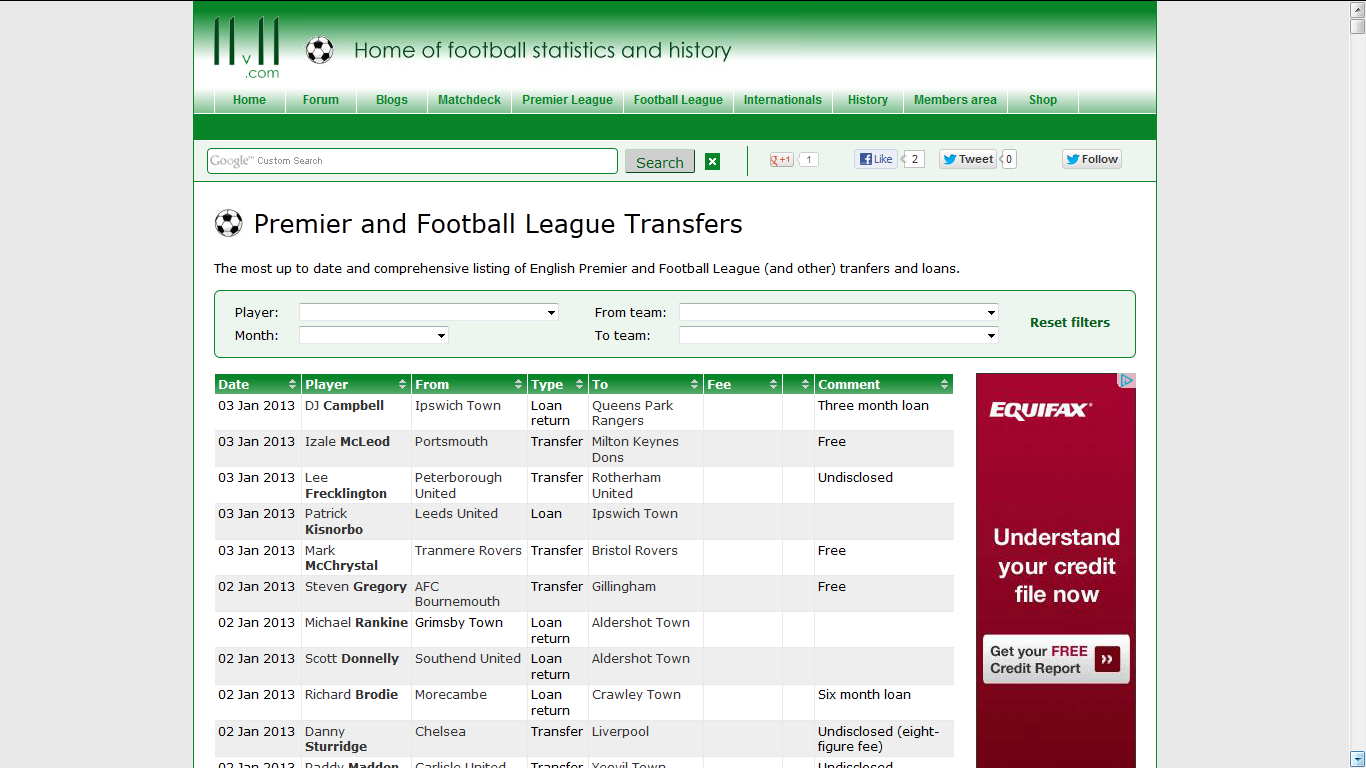

Well look at the frenzy that the transfer window which has just opened has produced.

Newspapers devote many column inches to telling us the players Premier League teams are targeting during the transfer window and where they may get them. Sky, not be outdone, has a transfer barometer and makes such a song and dance of the close of the transfer window on January 31 that it feels like the coming of a football Messiah.

This frenzy is now well established but few seem to notice how recent it is and how at one time it would have been considered very un-English. Indeed until a few years ago the very idea of a transfer window was anathema in this country. It was as much shunned as a winter break still is and the leading lights of the English game like Rick Parry made it clear that such an idea would not work and should be resisted at all costs.

But this country had to accept the idea because Europe wanted it. The transfer window that the English so hated would not have come about had the players not been encouraged by the Europeans. This included both the international players union and also the European Commission. It was this that led to long tortuous negotiations with the Commission leading to the introduction of the transfer window. It is fascinating to look back on how the discussions went.

The initial impetus for a transfer window had emerged because the highly paid players wanted to have total freedom of contract. Remember for all the huge sums top players get, wages that most of us can only dream about, they are to an extent still serfs. Modern players may be able to go on strike when they fall out with their clubs as Carlos Tevez effectively did last season. But while money can afford them hours on the golf course, or whatever else takes their fancy, they cannot just go and work somewhere else. Unlike us a footballer wanting to change jobs must get his present employer to agree to transfer his contract to his new club.

And in football it is an offense for a club seeking a player to contact the player directly. They have to channel any such inquiry through the player’s existing employer. In that remarkable football phrase they have to seek “permission” to talk to the player.

The reasons for such special rules are obvious enough. Football may claim to reflect society but it cannot operate as the rest of society. A club has to protect its team and it would be impossible for a manager to plan a team’s strategy if his players were always able to leave for another club whenever they wanted to.

Players arguing for total freedom of movement were aware of this and they pitched their argument cleverly. In essence they said the

transfer market was a manifestly unfair playing field. A player could not move until he came to the end of his contract. Yet a club could at anytime sell the player, if necessary a few months or even a few weeks after signing him on a long contract. What is more such movements of players between clubs took place all season long.

The players’ argument was if players could not move when they wanted to then clubs should also be restricted from moving players right

through the season. In essence they were making sure that if they could not break their shackles they could, at least, loosen them. English football did ban transfers but that ban only came into operation a few weeks before the close of a season and its origins lay in an attempt to stop clubs facing relegation manipulating the system to avoid the drop.

Now under European pressure English football had to accept two transfer windows, forcing club management to declare at the beginning of

the season what their squad was, with the right to change plans in January. The players accepted that they would still remain serfs but the price for that was the club management had to display some of the managerial skills they so often boasted about.

The best demonstration of the management use of the January transfer window is being shown by QPR, the bottom club in the Premier League. The owners accept their managerial mistake by sacking Mark Hughes. The new man Harry Redknapp then drops hints of what he might do during the January transfer window but being Harry he also tells us how difficult the transfer market is in January and how keen he is not to waste the owners money.

Clubs can also use the transfer window in January to get players on the cheap as Tottenham chairman Daniel Levy has just done with the

transfer of Zeki Fryers from Standard Leige. The 20 year old only moved there from Manchester United in the summer transfer window. Had Spurs bought him then they might have had to pay a lot more as special rules apply for buying players under the age of 23 from clubs where they learnt their football, as Fryers did at United. But such rules do not apply in Belgium the country that gave us Bosman. So Spurs to United’s fury have got a deal probably round £2 million cheaper. Tottenham have been clever as they often are in the transfer market but they are not the only club to make the most of transfer windows, particularly the January one.

But where English football has made things difficult for itself is that even as it has accepted changes directed by Europe it has done

so with such reluctance that it has made life difficult for English clubs, indeed leading to inflating money spent on transfer of players.

So consider how English football has come to terms with the Bosman ruling. Two years after that ruling, in March 1997, FIFA, which governs

international transfers announced it would change its “transfer rules to ensure equal treatment for all players moving between clubs within the European Union”. Basically this meant that players from non-EU countries who played for clubs within the EU would also be able to move to other clubs within the EU on free transfers once their contracts expired. But while other European countries eagerly went down the cosmopolitan route allowing young players from non EU countries to play for their clubs, without any restrictions English football imposed a crucial restriction.

It could do nothing about EU players moving to an English club, or a non-EU player from a EU club to an English one. But when it came to

non-EU players who did not have a EU club the British Home Office insisted that the players meet certain very specific criteria. This was that they were established players in their home countries having played in 75 per cent of thematches for their country in the previous two years. Also that the country concerned had to be in the top 75 FIFA world rankings. The Home office advised by the professional game, which includes representatives of the Professional Footballers Association, vets who can get a work permit. The net effect of this is that young talent from non EU countries cannot come to England.

Peter Ridsdale, now director of football at Preston North End, describes the effect this had when he found two talented young players from a non-EU country. “When I was at Leeds I had two 16 year olds from Australia Brett Emerton and Harry Kewell. Harry through his father qualified for a British passport and was no problem. But Brett did not and we could not sign him. He left to go to Holland playing for Feyenoord. In Europe they do not have the restrictions we have and in 2003 he came to Blackburn. Now he was coming from a EU club and allowed in but it meant Blackburn paid a transfer fee. This is money going out of the game in this country because we have rules which no other EU country has.”

The Blackburn fee was not disclosed but was believed to be £7 million. Feyenoord had signed him for £415,000. It was a classic illustration of English football embracing European change but doing so in a manner which did not always benefit English clubs.

Mihir Bose’s latest book: Game Changer How the English Premier League Came to Dominate the World has been published by Marshall Cavendish for £14.99

Follow Mihir on twitter @mihirbose