“I have hit rock bottom and I don’t see any way out of it,” Chelsea’s former European Cup Winners’ Cup winner, Alan Hudson

Alan Hudson is 62 years of age now but when he was the playmaker for a useful Chelsea team during the 1970s he was one of the Kings of the King’s Road. He was a household name, leading a lifestyle as flamboyant as the football he played over the 400-plus top-flight appearances he made as the creative force of clubs that consistently challenged for trophies.

Last year, Hudson told a UK national newspaper how he is as good as destitute, living in a hostel on a football pension worth £300 a month and £100 a week of disability benefits. “All I have is my laptop, a shaving bag and my crutches. I haven’t even got a change of clothes,” he told the Sunday Mirror.

Hudson’s life experience is by no means unique among footballers of his generation. They had the profiles of movie stars in their day but their earnings could not match their celebrity. How times have changed.

According to a report in the Argentinian newspaper La Nación last December, Messi has signed a deal guaranteeing him €19 million a year at Barcelona. Cristiano Ronaldo, the poster boy of Real Madrid, is said to earn €17 million. It is easy to see why.

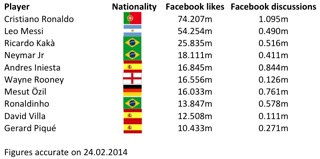

The current Ballon d’Or holder, Ronaldo has 74,204,966 likes on his Facebook page, facebook.com/Cristiano, and is involved in more than 1 million discussions. Facebook.com/LeoMessi has 54.2 million likes and is the subject of almost 0.5 million conversations. These statistics give an indication of the value of the very top players to brands aiming to engage with the 18- to 34-year-old, ‘digital-native’ demographic that traditional advertisers find so hard to reach.

But it is not only the Ballon d’Or finalists who enjoy enormous exposure.

Top 10 footballers by Facebook recognition

This gets to the heart of the question; What is a footballer worth? Clearly the fundamental valuation metric for any footballer, as an intangible asset on the club’s balance sheet, is what can he deliver in terms of revenue to the club.

For most that means how his on-pitch performances will contribute to the team’s end-of-season points total and cup-competition success, because that is what drives a large part of a club’s turnover. However, as the top clubs diversify their income streams beyond the stadium footprint and draw very significant revenues from commercial sources, there must be new considerations of how to price a player’s wages and transfer fee. The ability for individual players to generate widespread fan affection and, through that, commercial revenues for a football club are thus an increasingly important element of what they should be paid.

Wayne Rooney has scored only 10 goals and made nine assists in his 22 Premier League games for Manchester United this season, with a chance-conversion ratio of less than 14%. That is a long way from the 27 goals in 32 games he got in the 2011-12 season (with 17.2% chance conversion) or the 26 from 32 he scored in 2009-10 (14.3%).

With Robin van Persie recruited to lead the line, Rooney has not been playing in such an advanced role as he did during those seasons but many have commented on his diminished performance in what has been a difficult season for his team.

Yet last week his club announced Rooney had signed a £300,000-a-week contract that will ensure he remains a United ambassador following his retirement from the game.

Tim Crow, chief executive of the Synergy Sponsorship consultancy, believes Rooney’s digital profile has enhanced his earning power. “United have always been very good at it and before anyone else they were very clear about how they would turn their fans into customers,” said Crow.

“[United’s former chief executive] Peter Kenyon was derided for saying it but he was a long way ahead of his time with Customer Relationship Management databases. The social-media aspect is definitely a factor. The more [players] you have who can create a direct relationship with fans the better it is.

“Now footballers are creating their own brands and social-media communities and that can be monetised quickly.”

Footballers are now exploiting their personal brands in highly innovative ways. The latest venture to which Ronaldo has given his name, the GAME, combines the real and online worlds with a physical five-a-side tournament administered via an internet-based network of teams. With round-one matches having taken place since 26 January until 1 May this ambitious project so far has almost 32,000 teams signed up. (Even so, and despite widespread media coverage, the stockmarket-listed firm has not impressed investors: its share price has lost 60% of its value over the past 12 months.)

Having retired from playing in May last year, this month David Beckham (34 million Facebook likes) has gone one step further and put his name to an expansion team in Major League Soccer. He has purchased the MLS franchise in Miami alongside his long-term associate Simon Fuller and the Florida-based Marcelo Claure, president of the Brightstar Corporation, a wireless-network provider.

Beckham’s opportunity to invest was as a result of a savvy negotiation when, still aged only 31, the former Manchester United and Real Madrid midfielder unexpectedly announced he would swap European football for LA Galaxy.

Following a trail blazed by golfers like Arnold Palmer and basketballers like Michael Jordan (who happens also to own an expansion franchise in his sport) Beckham was football’s first true global player-megabrand. His career has clearly signalled the way for other top footballers to leverage their own profiles for future financial gain. But while players’ reputations can drive revenues for their clubs, they can also damage them. Two senior executives at Manchester United (42 million Facebook likes) made this clear in an interview with Strategic Risk magazine this month.

“One of the things that is most important is the assessment of character that goes in when we are looking at players to acquire,” said Phil Townsend, United’s director of communications.

“There is a concept of a Manchester United player – what does a Manchester United player do on the field? How does a Manchester United player behave off the field? And clearly while we don’t get it right every time it is a major part of what we do in terms of bringing players into the club.”

And when they do get it right, it is something the club can trade on commercially. The group managing director of United, Richard Arnold, said: “If you look at the stats for an average group of 18- to 30-year-old guys [and compare it with the Manchester United squad who have] no divorces, almost no alcohol related issues, certainly no drug related issues, they are certainly a very disciplined group of people and we are lucky to deal with that.”

So the opportunity for brands to be associated with something youthful, energetic yet wholesome is worth a premium of marketing dollars. With the extension of European club football to a ubiquitous global attraction, the game’s profile has grown, bringing the biggest commercial brands to the hoardings in modern, marketable stadiums. This has made the biggest clubs’ brands stronger and broadened the appeal of their biggest stars ever more. It is working out to be a highly positive feedback loop for everyone involved.

By no means is it finished yet but the speed of this transformation has already been remarkable. Hudson retired fewer than 30 years ago. It is truly a pity that all this has come too late for the likes of him.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1713287122labto1713287122ofdlr1713287122owedi1713287122sni@t1713287122tocs.1713287122ttam1713287122.