“First half. Last 10 minutes. Hundred per cent.” Former footballer Sam Sodje appears to promise a yellow card to order.

Betting has a tradition of accompanying football in England in the same way custard goes with English puddings. It just adds a bit of flavour to the proceedings. It is a guilty pleasure, nothing more. No harm done. Gambling is so much a part of the football culture in England that when last week the national-team manager, Roy Hodgson, discussed his team’s chances at next summer’s World Cup he entertained discussion of whom he would “have a tenner on”. No one batted an eyelid, because it’s all harmless fun. Anyone who says otherwise is a shrill killjoy, like some latter-day evangelist of the temperance movement.

But, in the context of recent news about what has been going on at several levels of the English game, Hodgson’s comments are wholly inappropriate. Investigations by the Sun on Sunday and the Daily Telegraph have shown how professional footballers appear to be fixing events in matches.

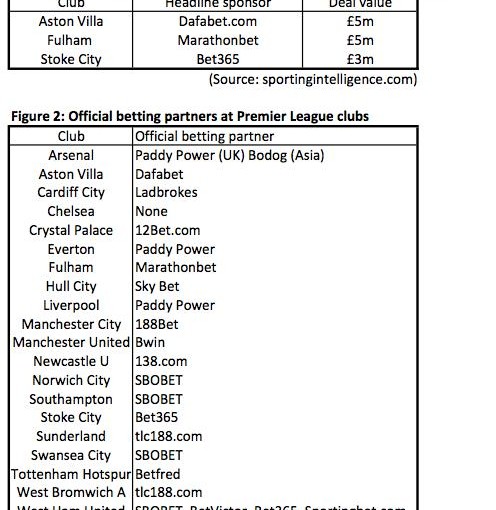

Now is the time to reappraise the complicated English relationship with the “harmless” flutter. The ubiquity of the betting companies whose advertisements fill the half- time breaks of every match covered on television has been very lucrative for football. Figures from the website sportingintelligence.com suggest that in title sponsorships alone Premier League clubs earn £13m a year from betting companies. Most whose principal sponsors are not the likes of Dafabet and Marathonbet otherwise have “betting partners” who are endorsed on their official websites and offer sponsored gambles to clubs’ fans in return for a fee payable to the club.

Only the six highest-profile Premier League clubs draw £1m-plus sums from their “official betting partnerships” and several must work hard through social-media channels to promote their sponsors in return for performance-related bonuses.

One club, Stoke City, has the deepest relationship of all with the bookmakers: not only is Bet365 its shirt sponsor, but also its owner, as the club is a group subsidiary company of the bookmaker. It is unthinkable that any such proprietary relationship of between a gambling operator and a sports participant could ever be permitted in US sport, for instance. The Football League, in whose competition the most recent scandalous revelations have emerged from, is itself sponsored by Sky Bet, another bookmaker. It means the gambling operator enters the language of the game, trumpeted every week as media print tables with the company’s logo and final-score bulletins carry results from the ‘Sky Bet Championship’. This serves unhelpfully to reinforce the ‘innocuous’ relationship between betting and football in the fan’s – and, as Hodgson’s ill-judged comments demonstrate, the player and manager’s – mind. It is worth noting that there are some contractual obligations on betting sponsors. A clause in the Premier League regulations stipulates gambling operators must “provide accurate and complete information forthwith to the League” if it wants to investigate alleged breaches of its rules. But this is an ineffectual tool for a number of reasons.

In 2006 a whistleblower who had previously worked for the bookmaker Victor Chandler claimed to have data from accounts belonging to Premier League players and managers. The account holders had allegedly bet on matches in their own competitions, in breach of football’s regulations. But Victor Chandler International [VCI] obtained a high-court injunction preventing the release of information about the accounts. “He wants to maintain his clients’ right to privacy,” said his then publicist, Max Clifford. “We were at the high court yesterday making sure no one could reveal their names.”

Paul Scotney is one of the top anti-corruption investigators in British sport and is now on the board of the Sports Betting Group, a policy organisation aimed at tackling corruption through betting. He told parliament last month how important betting and identity data are for sports investigators. Dismayingly he also told of the obstructions some gambling operators still place in the way of inquiries, years after the VCI case.

“Without this information you cannot carry out a meaningful investigation,” he said. “That is the crux of it. We need that information, and that is personal information.

“The situation we have now… is that some regulators voluntarily give us the information we want and are very co-operative. Some take the middle ground because they are unsure about what they can and cannot do, and they may give it and they may not.

“Then there are others which do not share at all. We have an inconsistent position, and without access to that data we cannot meaningfully investigate corruption in sport.” There is no way of knowing if the alleged breaches of regulations relating to the VCI accountholders amounted to anything more sinister. (And it is fair to say that Chandler would be unlikely to have exposed himself repeatedly to bets on matches involving account holders’ teams, given the substantial risk of manipulation.)

But the lack of transparency is deliberately obstructive and might give a desperado considering whether to engage in corrupt activity the sense of imperviousness to prosecution. Indeed, with ever-more-sophisticated forms of online gambling having sprung up over the intervening seven years since the VCI incident, players have access to far more layers than the traditional UK bookmakers.

And the £12,500 yellow-card negotiation involving the former Nigeria international defender Sam Sodje raises fears that what has been uncovered so far is merely the tip of an iceberg that might suggest the existence of a broad network of players at a number of professional clubs. (If the allegations about Sodje are proven it will be particularly depressing. He is of all people the product of a football family, along with his brothers Efe and Akpo, and if he has sought to betray the game that has provided them all with a living then where is its soul?)

Whether they know it or not, players who fix matches or events within them are the foot soldiers of international match-fixing rings who, according to sports anticorruption experts, have links with serious organised crime. The fixers do not place the bulk of their bets with onshore UK bookmakers but in Asian markets where the liquidity is deeper and where the regulatory scrutiny is much lighter.

How many of them would volunteer information to the authorities about the identities and activities of suspicious gamblers? Indeed, though they offer bets in the UK on UK sports markets, many of even the household-name bookmakers who generate the bulk of their profits from UK punters, pay little or no UK tax and have scant regulatory oversight in the UK.

Clearly those who do pay such taxes and bear the cost of an effective compliance regime are commercially disadvantaged in the value of the odds they can offer to punters. This encourages punters to seek the best odds with those offshore layers who do nothing to protect the game’s integrity.

It is a parasites’ charter, and that cannot be right.

Fortunately parliament is in the process of reviewing its arrangements with the bookmaking industry and is considering how to encourage the “onshoring” of bookmakers currently operating oversees. The debates in parliamentary hearings involving stakeholders such as the Premier League have shown how fraught the situation is.

A regular dialogue between the regulator and the operators under licence is essential for the smooth running of a regulated system. But Peter Howitt, chief executive of the Gibraltar Betting and Gaming Association, warns about the risk of giving an “imprimatur” or kitemark to gambling operators who have no real UK interface and who obtain a UK gaming licence. This leads to questions of just how much due diligence is conducted by clubs who agree to their marques being used on Asian layers’ websites in return for the six-figure sum in sponsorship that might pay a reserve full-back’s annual wage.

Before conferring the legitimacy of their branding to those remote gambling operators, do the clubs first work hard to satisfy themselves about the integrity protections they have put in place? Are they even qualified to do so? Or is it merely a naked cash grab? Scotney’s remarks about the weakness of some layers’ commitment to the game’s integrity suggest we know the answer. This puts clubs’ commercial teams at odds with the League, which has an obligation to safeguard the sanctity of the competition in perpetuity without regard to annual On-Target Earnings bonus schemes.

The Premier League’s general secretary, Nic Coward, summed up what is required of the government as it deliberates what to do next. “It [is] true of any regulated sector that there need to be clear regulations in place so that the sector and stakeholders with an interest in the sector understand what they are,” he said. “That they are monitored; that there is an effective compliance regime; and that there are real enforcement provisions behind it.”

Currently too few, if any, of those boxes are ticked. As the National Crime Agency’s arrests have shown, it is high time for law makers and enforcers to act. For if not, it will be easier to deliver yellow cards to order on the football pitch than for miscreant bookmakers to be issued with cautions about their activities.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1713549178labto1713549178ofdlr1713549178owedi1713549178sni@t1713549178tocs.1713549178ttam1713549178.