“Ah! There is nothing like staying at home for real comfort.” Jane Austen, Emma

Jane Austen’s fourth novel was published on Christmas Day in 1815 the Vienna peace accord had brought the Napoleonic wars to a close. With it began a century-long era of British commercial dominance through an empire whose roots had already begun to take hold with territories in Newfoundland, the Caribbean, west and South Africa, India and Australia.

King George III’s empire could not have survived without the buccaneering spirit of the British common man. Were he to be a stay-at-home recluse, there would have been no Royal Navy, no far-flung trading posts, no intrepid explorations of the jungle, the desert and the high seas.

It was not that the British people are uniquely itched by wanderlust. It was of course rather that economic circumstances at home at the time of the Industrial Revolution were routinely so unpleasant as to force men to seek a better life overseas.

Two hundred years later it is of course the same economic principle that prompts footballers to move countries today. Except the situation is now reversed: migration of foreigners into English football far outweighs those who move overseas from England.

This has led to a tremendous amount of handwringing in England. Mark Ogden demonstrated in the Daily Telegraph on Tuesday how only 24 English players were registered for Champions League football this season, and only 12 of them had played any football at all during their eight games English sides had played at the time of writing. This, noted Ogden, was fewer than Israeli and Belarussian players had registered.

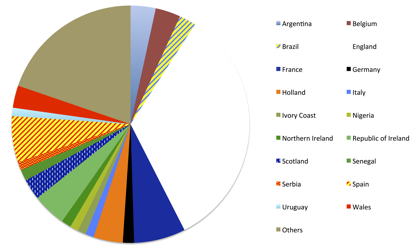

This has led to complaints about perceived deficiencies in the English coaching system. But it is not without effort on behalf of the authorities. Since 2012 the Premier League has been running the Elite Player Performance Plan, under which there are now 40 academies in England. It is too early to say whether this is having an effect on the quality of the players being developed but it is fair to say the diminishing quantity is not in doubt. When the Premier League was launched in 1992, almost seven in 10 of all players were English. Now, as the (admittedly rather ugly) chart above shows, two in three are not English.

This has prompted the Football Association chairman, Greg Dyke, to describe English players as an “endangered species”. For the past five years English clubs have been obliged to carry eight Englishmen in their 25-man squads. Yet the number of English players in Premier League teams has continued to fall. Dyke’s answer is for more regulation, raising the quota to 12. But is the cure for a failed rule more of the same?

I would contend that it is not. For as is very often the case with well-intentioned regulations, there are unintended economic consequences that end up reinforcing the problems the regulations are designed to overcome. But first of all, let’s look at why the Premier League is so stuffed with foreign players. The reason is very obvious indeed: it is a question of money.

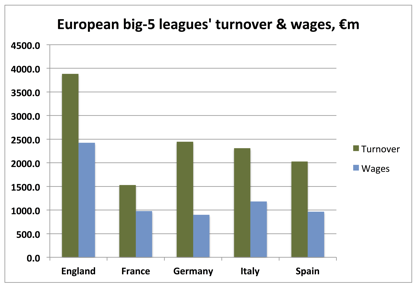

In 2013-14, the most-recent season for which league-wide financial data are available, the 20 Premier League clubs turned over an aggregate £3.261 billion. In euro terms that amounted to €3.881 billion. To put that sum into context, it was over 8% more than the 40 clubs in the Spanish and French leagues combined could generate. Given that the general expenses of running a football club do not move all that much, however big the revenues, this gave English clubs exponentially more margin to invest in player wages over their continental rivals, as demonstrated in the chart below.

The amount Premier League clubs paid in wages was equivalent to 85.2% of the combined salary bills of the 58 clubs in France, Spain and Germany. This naturally makes England the destination of choice for players and their agents, accounting for the 57 different nationalities playing in the Premier League.

But all this money sloshing around has another effect, and it is one that is exacerbated as a result of the regulations the FA and the Premier League regulations. With nationality-based player quotas in place, English players come at a premium, meaning the best of them can expect to earn disproportionately more in England. Even those who are not in the international elite, many just teenagers, are earning sums to make them for life.

Looking back at the 2013-14 season, Manchester City had six English players in their squad. (The rules over home-grown players allowed foreign players developed at English clubs to count towards the quota, so Welshman Emyr Huws and the Frenchman Gaël Clichy qualified.) Among them only Joe Hart, the England goalkeeper, was a first-choice player. The other five, Micah Richards, James Milner, Jack Rodwell, Richard Wright and Joleon Lescott, started 23 matches between them – fewer than five each on average.

Only three of them – Milner, Rodwell and Lescott – were acquired for transfer fees (Wright was a free transfer and Richards developed at City), at a combined cost of £45.15 million, according to Transfermarkt.com. Yet in a combined 25 completed seasons at City, those five English players made fewer than 400 appearances: less than 16 per season each on average.

So what kept them there? It surely all goes back to the money. Those players were participating in a City wage bill in excess of £205 million. They were some of the best English players of their generation but they were prepared to sacrifice regular first-team football for the riches on offer on City’s bench.

The same applies for more-modest talents at many other top-flight clubs. Players who might develop their skills better by playing regular top-division football at, say, Celta Vigo or Levante in Spain or Guingamp or Nantes in France, where the wage bills were about €17 million or €18 million a year in 2013-14, prefer to warm benches at English clubs paying their players 4.5 times as much.

This is English football’s affliction. It is not that the opportunity does not exist for players to play – there are 78 other top-division clubs in the big-five European leagues – it is that the incentives not to leave England in search of first-team football are too strong.

Young Englishmen whose path to the first team is blocked by the two-thirds of players at Premier League clubs who have come from overseas should model themselves on a 21-year-old compatriot of theirs. Eric Dier was born in Cheltenham but spent his formative years at Sporting Lisbon’s academy after his parents moved to Portugal when he was 10 years old. After 26 first-team matches at Cristiano Ronaldo’s old club, Dier was back in England with Tottenham Hotspur. Signed as a defender, he has become a first-choice holding midfielder and played all but 19 minutes for Spurs this season in all competitions and has every reason to believe he could be England’s holding midfielder at the Euros next summer.

Where English football is at fault is not in the players it is developing or in the lack of quotas it imposes; quite the contrary. English football should try scrapping the Premier League quota altogether. Only that would overturn the skewed economics of the English games, where players are paid disproportionately not to play just on the colour of their passport. By suppressing the wages on offer to English players, it would force more to seek a living in the first teams of clubs overseas, while the very best of them – the likes of Raheem Sterling or Theo Walcott – would remain here prospering in the top English clubs.

Indeed, English players might not be finding a path to the top in their own country but even now there is nothing stopping them following their 19th Century forebears and seeking opportunities overseas. Nothing, that is, except the real comforts of home.

Journalist and broadcaster Matt Scott wrote the Digger column for The Guardian newspaper for five years and is now a columnist for Insideworldfootball. Contact him at moc.l1712689755labto1712689755ofdlr1712689755owedi1712689755sni@t1712689755tocs.1712689755ttam1712689755.